Update, 2018-08-24: For a more complete, formal discussion of consistency models, see jepsen.io.

Network partitions are going to happen. Switches, NICs, host hardware, operating systems, disks, virtualization layers, and language runtimes, not to mention program semantics themselves, all conspire to delay, drop, duplicate, or reorder our messages. In an uncertain world, we want our software to maintain some sense of intuitive correctness.

Well, obviously we want intuitive correctness. Do The Right Thing(TM)! But what exactly is the right thing? How might we describe it? In this essay, we’ll take a tour of some “strong” consistency models, and see how they fit together.

Correctness

There are many ways to express an algorithm’s abstract behavior–but just for now, let’s say that a system is comprised of a state, and some operations that transform that state. As the system runs, it moves from state to state through some history of operations.

For instance, our state might be a variable, and the operations on the state could be the writes to, and reads from, that variable. In this simple Ruby program, we write and read a variable several times, printing it to the screen to illustrate the reads.

x = "a"; puts x; puts x

x = "b"; puts x

x = "c"

x = "d"; puts x

We already have an intuitive model of this program’s correctness: it should print “aabd”. Why? Because each of the statements happen in order. First we write the value a, then read the value a, then read the value a, then write the value b, and so on.

Once we set a variable to some value, like a, reading it should return a, until we change the value again. Reading a variable returns the most recently written value. We call this kind of system–a variable with a single value–a register.

We’ve had this model drilled into our heads from the first day we started writing programs, so it feels like second nature–but this is not the only way variables could work. A variable could return any value for a read: a, d, or the moon. If that happened, we’d say the system was incorrect, because those operations don’t align with our model of how variables are supposed to work.

This hints at a definition of correctness for a system: given some rules which relate the operations and state, the history of operations in the system should always follow those rules. We call those rules a consistency model.

We phrased our rules for registers as simple English statements, but they could be arbitrarily complicated mathematical structures. “A read returns the value from two writes ago, plus three, except when the value is four, in which case the read may return either cat or dog” is a consistency model. As is “Every read always returns zero”. We could even say “There are no rules at all; every operation is permitted”. That’s the easiest consistency model to satisfy; every system obeys it trivially.

More formally, we say that a consistency model is the set of all allowed histories of operations. If we run a program and it goes through a sequence of operations in the allowed set, that particular execution is consistent. If the program screws up occasionally and goes through a history not in the consistency model, we say the history was inconsistent. If every possible execution falls into the allowed set, the system satisfies the model. We want real systems to satisfy “intuitively correct” consistency models, so that we can write predictable programs.

Concurrent histories

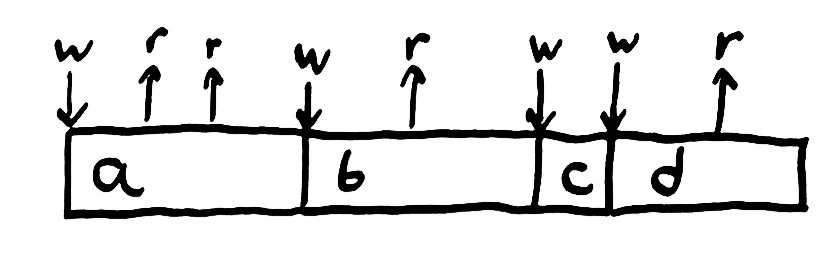

Now imagine a concurrent program, like one written in Node.js or Erlang. There are multiple logical threads of control, which we term “processes”. If we run a concurrent program with two processes, each of which works with the same register, our earlier register invariant could be violated.

There are two processes at work here: call them “top” and “bottom”. The top process tries to write a, read, read. The bottom process, meanwhile, tries to read, write b, read. Because the program is concurrent, the operations from these two processes could interleave in more than one order–so long as the operations for a single process happen in the order that process specifies. In this particular case, top writes a, bottom reads a, top reads a, bottom writes b, top reads b, and bottom reads b.

In this light, the concept of concurrency takes on a different shape. We might imagine every program as concurrent by default–when executed, operations could happen in any order. A thread, a process–in the logical sense, anyway–is a constraint over the history: operations belonging to the same thread must take place in order. Logical threads impose a partial order over the allowed operations.

Even with that order, our register invariant–from the point of view of an individual process–no longer holds. The process on top wrote a, read a, then read b–which is not the value it wrote. We must relax our consistency model to usefully describe concurrency. Now, a process is allowed to read the most recently written value from any process, not just itself. The register becomes a place of coordination between two processes; they share state.

Light cones

Howerver, this is not the full story: in almost every real-world system, processes are distant from each other. An uncached value in memory, for instance, is likely on a DIMM thirty centimeters away from the CPU. It takes light over a full nanosecond to travel that distance–and real memory accesses are much slower. A value on a computer in a different datacenter could be thousands of kilometers–hundreds of milliseconds–away. We just can’t send information there any faster; physics, thus far, forbids it.

This means our operations are no longer instantaneous. Some of them might be so fast as to be negligible, but in full generality, operations take time. We invoke a write of a variable; the write travels to memory, or another computer, or the moon; the memory changes state; a confirmation travels back; and then we know the operation took place.

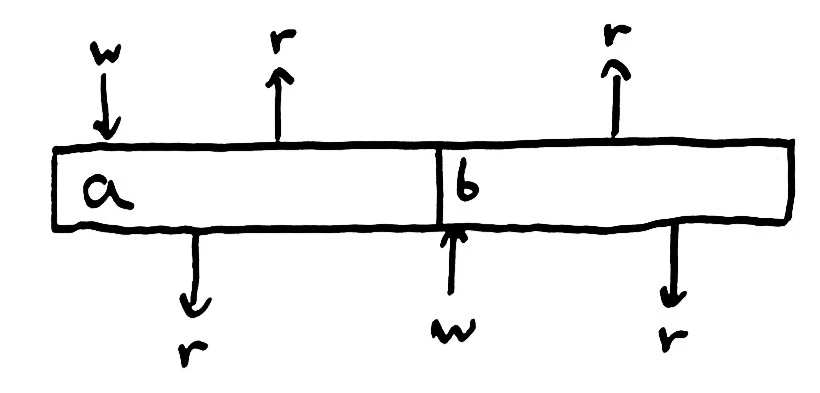

The delay in sending messages from one place to another implies ambiguity in the history of operations. If messages travel faster or slower, they could take place in unexpected orders. Here, the bottom process invokes a read when the value is a. While the read is in flight, the top process writes b–and by happenstance, its write arrives before the read. The bottom process finally completes its read and finds b, not a.

This history violates our concurrent register consistency model. The bottom process did not read the current value at the time it invoked the read. We might try to use the completion time, rather than the invocation time, as the “true time” of the operation, but this fails by symmetry as well; if the read arrives before the write, the process would receive a when the current value is b.

In a distributed system–one in which it takes time for an operation to take place–we must relax our consistency model again; allowing these ambiguous orders to happen.

How far must we go? Must we allow all orderings? Or can we still impose some sanity on the world?

Linearizability

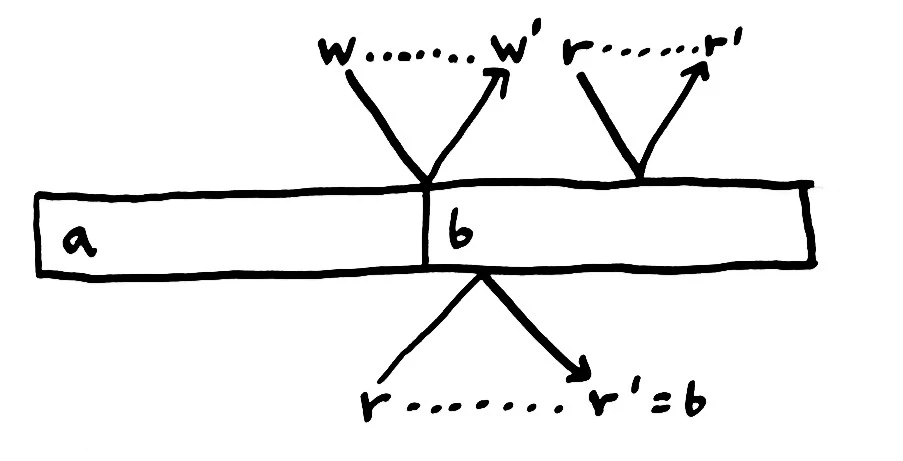

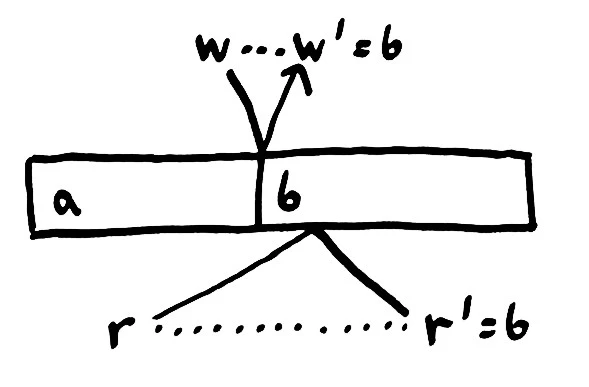

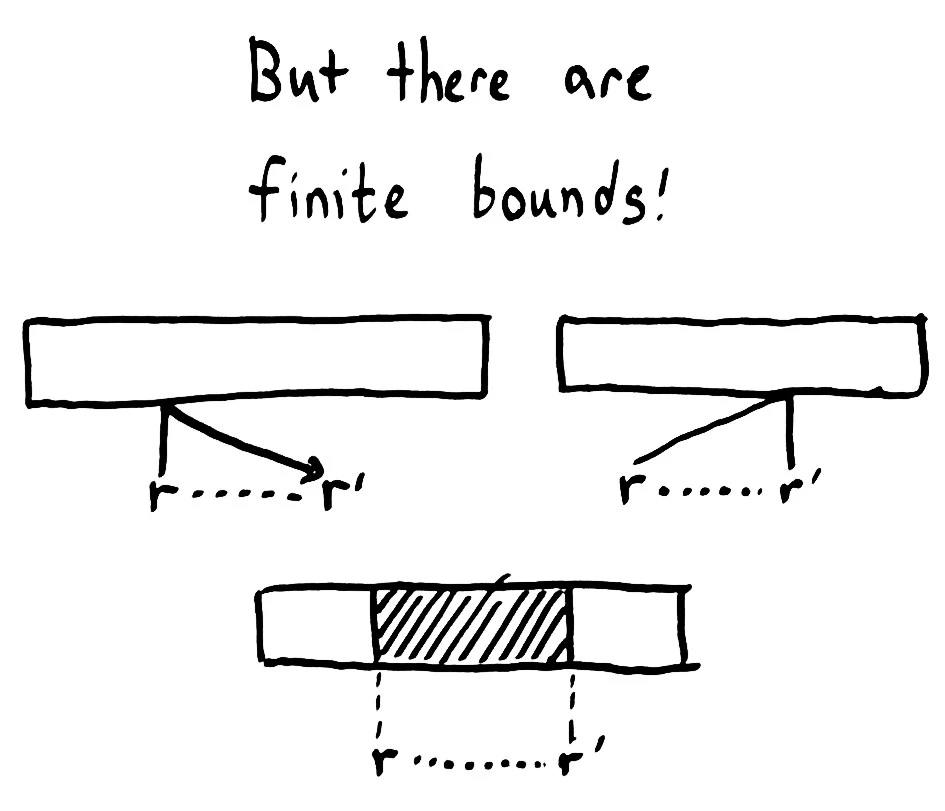

On careful examination, there are some bounds on the order of events. We can’t send a message back in time, so the earliest a message could reach the source of truth is, well, instantly. An operation cannot take effect before its invocation.

Likewise, the message informing the process that its operation completed cannot travel back in time, which means that no operation may take effect after its completion.

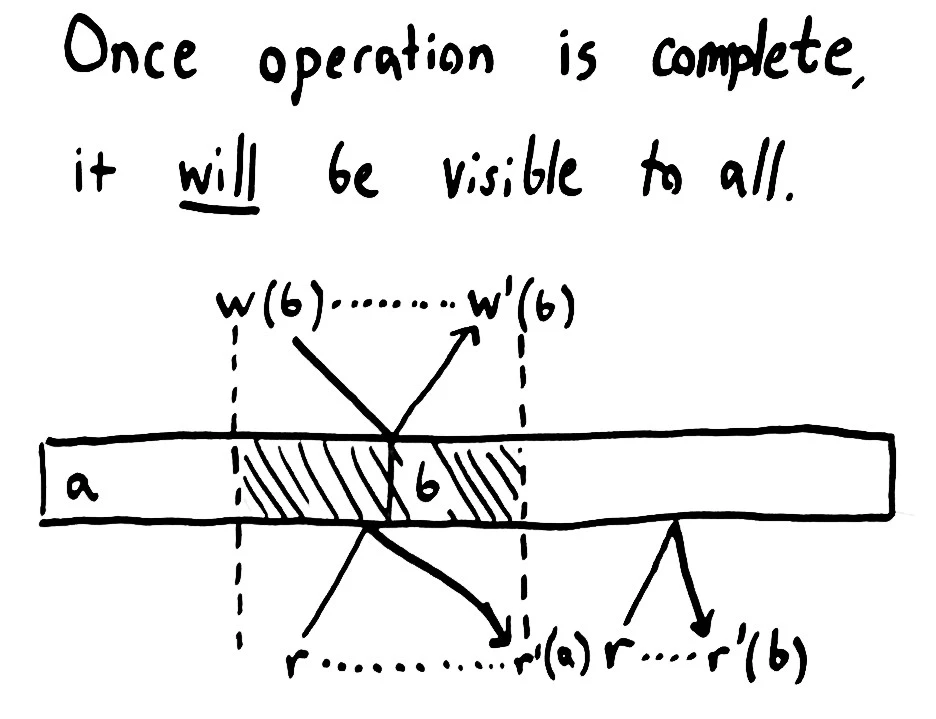

If we assume that there is a single global state that each process talks to; if we assume that operations on that state take place atomically, without stepping on each other’s toes; then we can rule out a great many histories indeed. We know that each operation appears to take effect atomically at some point between its invocation and completion.

We call this consistency model linearizability; because although operations are concurrent, and take time, there is some place–or the appearance of a place–where every operation happens in a nice linear order.

The “single global state” doesn’t have to be a single node; nor do operations actually have to be atomic. The state could be split across many machines, or take place in multiple steps–so long as the external history, from the point of view of the processes, appears equivalent to an atomic, single point of state. Often, a linearizable system is made up of smaller coordinating processes, each of which is itself linearizable; and those processes are made up of carefully coordinated smaller processes, and so on, down to linearizable operations provided by the hardware.

Linearizability has powerful consequences. Once an operation is complete, everyone must see it–or some later state. We know this to be true because each operation must take place before its completion time, and any operation invoked subsequently must take place after the invocation–and by extension, after the original operation itself. Once we successfully write b, every subsequently invoked read must see b–or some later value, if more writes occur.

We can use the atomic constraint of linearizability to mutate state safely. We can define an operation like compare-and-set, in which we set the value of a register to a new value if, and only if, the register currently has some other value. We can use compare-and-set as the basis for mutexes, semaphores, channels, counters, lists, sets, maps, trees–all kinds of shared data structures become available. Linearizability guarantees us the safe interleaving of changes.

Moreover, linearizability’s time bounds guarantee that those changes will be visible to other participants after the operation completes. Hence, linearizability prohibits stale reads. Each read will see some current state between invocation and completion; but not a state prior to the read. It also prohibits non-monotonic reads–in which one reads a new value, then an old one.

Because of these strong constraints, linearizable systems are easier to reason about–which is why they’re chosen as the basis for many concurrent programming constructs. All variables in Javascript are (independently) linearizable; as are volatile variables in Java, atoms in Clojure, or individual processes in Erlang. Most languages have mutexes and semaphores; these are linearizable too. Strong assumptions yield strong guarantees.

But what happens if we can’t satisfy those assumptions?

Sequential consistency

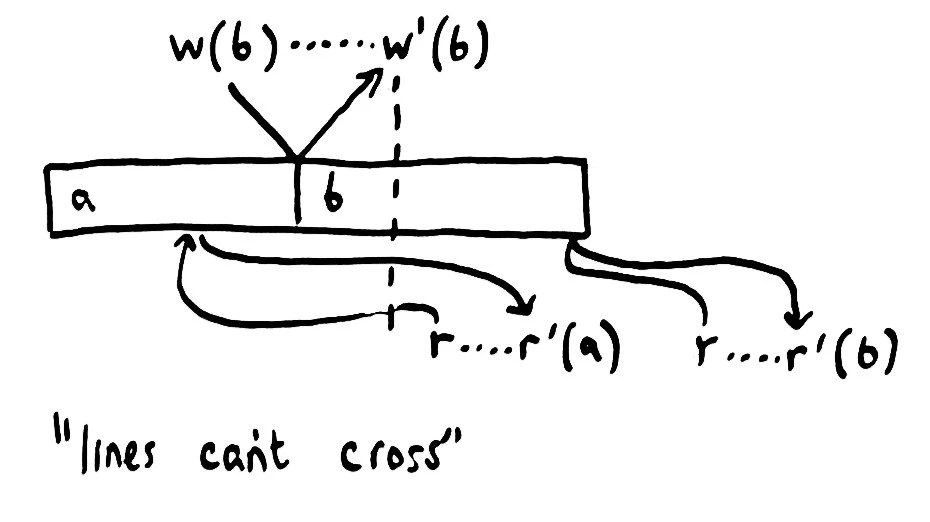

If we allow processes to skew in time, such that their operations can take effect before invocation, or after completion–but retain the constraint that operations from any given process must take place in that process’ order–we get a weaker flavor of consistency: sequential consistency.

Sequential consistency allows more histories than linearizability–but it’s still a useful model: one that we use every day. When a user uploads a video to YouTube, for instance, YouTube puts that video into a queue for processing, then returns a web page for the video right away. We can’t actually watch the video at that point; the video upload takes effect a few minutes later, when it’s been fully processed. Queues remove synchronous behavior while (depending on the queue) preserving order.

Many caches also behave like sequentially consistent systems. If I write a tweet on Twitter, or post to Facebook, it takes time to percolate through layers of caching systems. Different users will see my message at different times–but each user will see my operations in order. Once seen, a post shouldn’t disappear. If I write multiple comments, they’ll become visible sequentially, not out of order.

Causal consistency

We don’t have to enforce the order of every operation from a process. Perhaps, only causally related operations must occur in order. We might say, for instance, that all comments on a blog post must appear in the same order for everyone, and insist that any reply be visible to a process only after the post it replies to is visible. If we encode those causal relationships like “I depend on operation X” as an explicit part of each operation, the database can delay making operations visible until it has all the operation’s dependencies.

This is weaker than ordering every operation from the same process–operations from the same process with independent causal chains could execute in any relative order–but prevents many unintuitive behaviors.

Serializable consistency

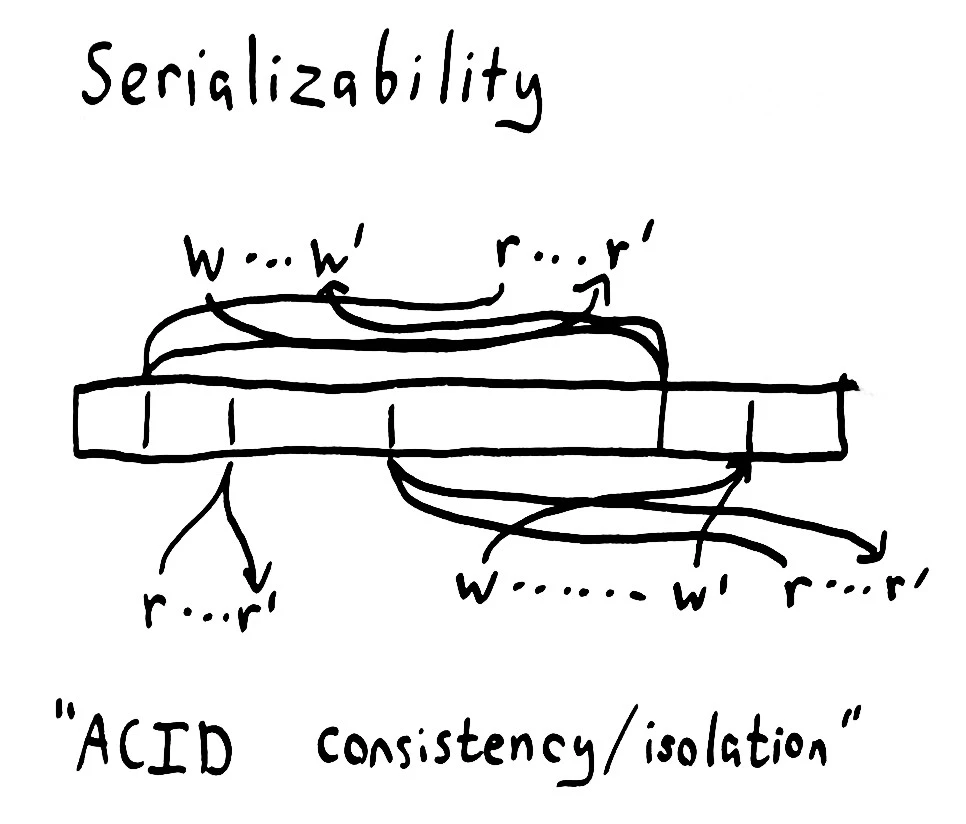

If we say that the history of operations is equivalent to one that took place in some single atomic order–but say nothing about the invocation and completion times–we obtain a consistency model known as serializability. This model is both much stronger and much weaker than you’d expect.

Serializability is weak, in the sense that it permits many types of histories, because it places no bounds on time or order. In the diagram to the right, it’s as if messages could be sent arbitrarily far into the past or future, that causal lines are allowed to cross. In a serializable database, a transaction like read x is always allowed to execute at time 0, when x had not yet been initialized. Or it might be delayed infinitely far into the future! The transaction write 2 to x could execute right now, or it could be delayed until the end of time, never appearing to occur.

For instance, in a serializable system, the program

x = 1

x = x + 1

puts x

is allowed to print nil, 1, or 2; because the operations can take place in any order. This is a surprisingly weak constraint! Here, we assume that each line represents a single operation and that all operations succeed.

On the other hand, serializability is strong, in the sense that it prohibits large classes of histories, because it demands a linear order. The program

print x if x = 3

x = 1 if x = nil

x = 2 if x = 1

x = 3 if x = 2

can only be ordered in one way. It doesn’t happen in the same order we wrote, but it will reliably change x from nil -> 1 -> 2 -> 3, and finally print 3.

Because serializability allows arbitrary reordering of operations (so long as the order appears atomic), it is not particularly useful in real applications. Most databases which claim to provide serializability actually provide strong serializability, which has the same time bounds as linearizability. To complicate matters further, what most SQL databases term the SERIALIZABLE consistency level actually means something weaker, like repeatable read, cursor stability, or snapshot isolation.

Consistency comes with costs

We’ve said that “weak” consistency models allow more histories than “strong” consistency models. Linearizability, for example, guarantees that operations take place between the invocation and completion times. However, imposing order requires coordination. Speaking loosely, the more histories we exclude, the more careful and communicative the participants in a system must be.

You may have heard of the CAP theorem, which states that given consistency, availability, and partition tolerance, any given system may guarantee at most two of those properties. While Eric Brewer’s CAP conjecture was phrased in these informal terms, the CAP theorem has very precise definitions:

-

Consistency means linearizability, and in particular, a linearizable register. Registers are equivalent to other systems, including sets, lists, maps, relational databases, and so on, so the theorem can be extended to cover all kinds of linearizable systems.

-

Availability means that every request to a non-failing node must complete successfully. Since network partitions are allowed to last arbitrarily long, this means that nodes cannot simply defer responding until after the partition heals.

-

Partition tolerance means that partitions can happen. Providing consistency and availability when the network is reliable is easy. Providing both when the network is not reliable is provably impossible. If your network is not perfectly reliable–and it isn’t–you cannot choose CA. This means that all practical distributed systems on commodity hardware can guarantee, at maximum, either AP or CP.

“Hang on!” you might exclaim. “Linearizability is not the end-all-be-all of consistency models! I could work around the CAP theorem by providing sequential consistency, or serializability, or snapshot isolation!”

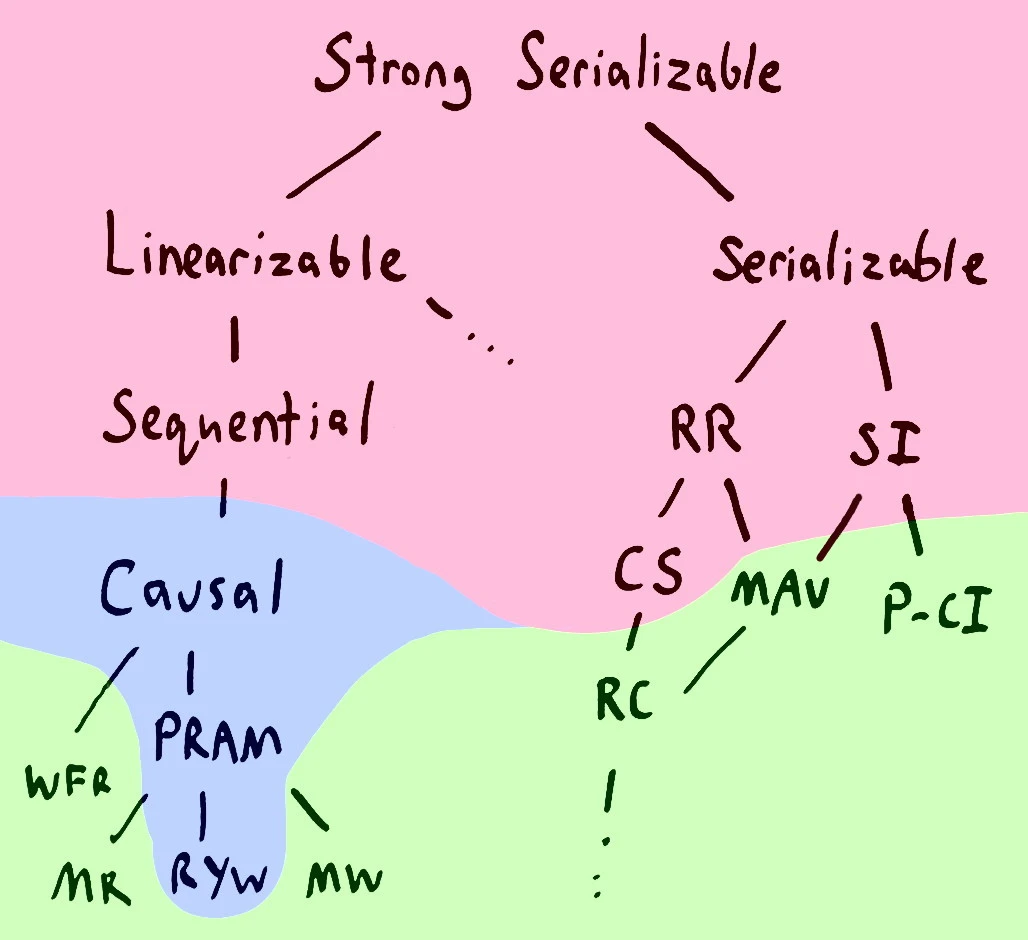

This is true; the CAP theorem only says that we cannot build totally available linearizable systems. The problem is that we have other proofs which tell us that you cannot build totally available systems with sequential, serializable, repeatable read, snapshot isolation, or cursor stability–or any models stronger than those. In this map from Peter Bailis’ Highly Available Transactions paper, models shaded in red cannot be fully available.

If we relax our notion of availability, such that client nodes must always talk to the same server, some types of consistency become achievable. We can provide causal consistency, PRAM, and read-your-writes consistency.

If we demand total availability, then we can provide monotonic reads, monotonic writes, read committed, monotonic atomic view, and so on. These are the consistency models provided by distributed stores like Riak and Cassandra, or ANSI SQL databases on the lower isolation settings. These consistency models don’t have linear orders like the diagrams we’ve drawn before; instead, they provide partial orders which come together in a patchwork or web. The orders are partial because they admit a broader class of histories.

A hybrid approach

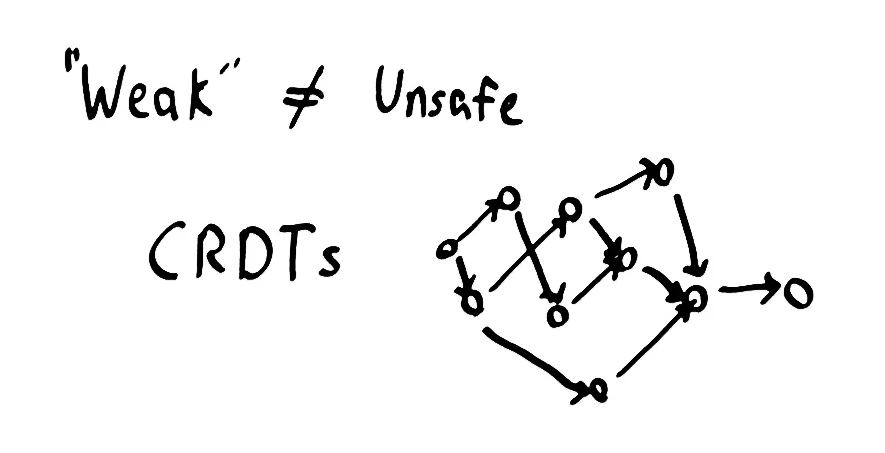

Some algorithms depend on linearizability for safety. If we want to build a distributed lock service, for instance, linearizability is required; without hard time boundaries, we could hold a lock from the future or from the past. On the other hand, many algorithms don’t need linearizability. Eventually consistent sets, lists, trees, and maps, for instance, can be safely expressed as CRDTs even in “weak” consistency models.

Stronger consistency models also tend to require more coordination–more messages back and forth–to ensure their operations occur in the correct order. Not only are they less available, but they can also impose higher latency constraints. This is why modern CPU memory models are not linearizable by default–unless you explicitly say so, modern CPUs will reorder memory operations relative to other cores, or worse. While more difficult to reason about, the performance benefits are phenomenal. Geographically distributed systems, with hundreds of milliseconds of latency between datacenters, often make similar tradeoffs.

So in practice, we use hybrid data storage, mixing databases with varying consistency models to achieve our redundancy, availability, performance, and safety objectives. “Weaker” consistency models wherever possible, for availability and performance. “Stronger” consistency models where necessary, because the algorithm being expressed demands a stricter ordering of operations. You can write huge volumes of data to S3, Riak or Cassandra, for instance, then write a pointer to that data, linearizably, to Postgres, Zookeeper or Etcd. Some databases admit multiple consistency models, like tunable isolation levels in relational databases, or Cassandra and Riak’s linearizable transactions, which can help cut down on the number of systems in play. Bottom line, though: anyone who says their consistency model is the only right choice is likely trying to sell something. You can’t have your cake and eat it too.

Armed with a more nuanced understanding of consistency models, I’d like to talk about how we go about verifying the correctness of a linearizable system. In the next Jepsen post, we’ll discuss the linearizability checker I’ve built for testing distributed systems: Knossos.

For a more formal definition of these models, try Dziuma, Fatourou, and Kanellou’s Survey on consistency conditions

Quick clarification: are you assuming something less conservative than potential causality (happens-before) while referring to “operations from the same process with independent causal chains”? I’m having a hard time thinking of a case where any two operations from the same machine are independent (concurrent) under potential causality, since one must have happened before the other.