This history is also available as a PDF or EPUB, which may be more pleasant for reading. You can also download the full BibTeX database for this work. If you have a story you’d like to share, you can email aphyr+leather-history@aphyr.com.

Bay Area Reporter, 1979The 1979 Gay Freedom Day Committee will apparently take the advice of its March Subcommittee and not attempt to bar persons who appear in chains, leather and other bondage symbolism in the eighth annual parade on June 24.

Several of the core of 60 people who have participated in this year’s planning meetings had objected to a 1978 “parade” occurrence. Some “S&M” entries had immediately followed Women Opposed to Violence and Pornography in the Media.

Bondage symbolism, objectors this year contend, provides not only sensation for non-Gay media coverage, but also emits a message contrary to the freedom theme of Gay Pride Week. Thus, they proposed a ban on leather and chains for this year’s celebration. The 1977 and 1978 events in San Francisco attracted 250,000 to 300,000 people and received national publicity.

However, a majority of the GFDC had decided that the “freedom” theme itself requires that people be allowed the attire of their choice.

Many subcommittee members see a parallel between this latest controversy and another of several years’ standing involving men in female attire (“drag”). A 1976 guideline on sexism (adopted also by succeeding committees) resolved that “dressing in drag on the part of either sex is not sexist of itself” and is offensive only if it “demeans women or is degrading to Gay men.”

Introduction

The argument goes like this.

Kink, leather, and BDSM do not belong at Pride. First, they aren’t actually LGBTQ: kink is also practiced by straight people (Baker-Jordan, 2021). Moreover, those queer people who do display kink at Pride expose vulnerable people to harmful symbols and acts. They wear pup hoods and rubber bodices, they dress in studded codpieces and leather harnesses, they sport floggers, handcuffs, and nipple clamps (lesbiansofpower, 2021; stellar_seabass, 2021). Some demonstrate kinky acts: they crack whips in the parade and chain themselves up on floats. Some have sex in public (kidpiratez, 2021).

These displays harm three classes of people. Children (and the larger class of minors, e.g. those under 18 or 21) are innocent and lack the sophistication to process what they are seeing: exposure to kink might frighten them or distort their normal development (Angel, 2021; Barrie, 2021). Asexual people, especially those who are sex-repulsed, may suffer emotional harm by being confronted with overt displays of sexuality (Dusty, 2021; roseburgmelissa, 2021). Finally, those with trauma may be triggered by these displays (stymstem, 2021). These hazards exclude vulnerable people from attending Pride: kink is therefore a barrier to accessibility (RiLo_10, 2021; Vaush, 2021).

Consent is key to healthy BDSM practice, but the public did not consent to seeing these sexual displays (Baker-Jordan, 2021; busytoebeans, 2021; prettycringey, 2021). By wearing leather harnesses and chaining each other up in broad daylight, kinksters have unethically involved non-consenting bystanders in a BDSM scene for their own (likely sexual) gratification (anemersi, 2021; Bartosch, 2020; Xavier’s Online, 2021a, 2021b). The lack of consent to these sexual displays constitutes a form of sexual assault (PencilApocalyps, 2021). At worst, the fact that children may be present in the crowd makes these displays pedophilia (Rose, 2021), and (if one is so inclined) exemplifies the moral degeneracy of the entire LGBTQ community and impending collapse of civilization (Dreher, 2021; Keki, 2019)1.

Not everyone holds all of these views, or holds them to this degree; this is a synthesis of one pole in a diverse and vigorous debate. Nevertheless, calls to ban kink at Pride remain a mainstay of Twitter and Tumblr every June. To some extent this position is advanced by anti-gay reactionaries on 4chan and Telegram channels (Piper, 2021), but this is not the whole story: many opposed to kink at Pride identify themselves as queer, or at least queer-friendly (Mahale, 2021).

Queer people arguing against kink at Pride generally seem to be younger—often in their teens and early twenties. They may lack significant experience attending Pride. There is sometimes a belief that young people, leather, and overt sexuality have not historically coexisted at Pride, and the “arrival” of one requires the removal of another. Though many kink-at-Pride opponents have some familiarity with (and even interest in) kink, few evince a deep understanding of who these kinky marchers are, where they’ve been, or what they represent. Almost nobody seems to realize that the struggle over public visibility of leather people in the queer community has been ongoing for over fifty years (Chingy L, 2019; Haasch & López, 2021).

In fact, leather people and organizations were significant contributors to the LGBTQ movement and to Pride specifically: they were present at riots like Compton’s & Stonewall, and served as organizers, marchers, writers, and fundraisers from the very first Prides on (Bruce, 2016; Limoncelli, 2005; S. K. Stein, 2021; Teeman, 2020). In NYC, Leather Pride Night was for many years the single largest financial contributor to Pride, and the leather community fielded some of the largest contingents in New York and Los Angeles (P. Douglas, 1995; Los Angeles Leather History, 2021; D. Stein, 1991a). Leather communities mobilized significant financial and direct aid for people with HIV during the health crisis (P. Douglas, 1995; Mr. Marcus, 1990a, 1992a). Leather activists helped organize and marched in full gear at the 1987 and 1993 Marches on Washington, and led whip-cracking demos at Pride in San Francisco, Dallas, and New York (Califia, 1994b; B. Douglas, 1987, 1995b; NLA: Houston, 1993; S. K. Stein, 2021).

However, the relationship between queer leather and the larger LGBTQ community has not been easy. Despite facing similar forms of stigma and oppression from police and society at large, Pride organizers actually did try to ban leather from Pride. Queer leather groups were denied access to feminist and queer community centers, and had their writing and art excluded from bookstores and periodicals during the Lesbian Sex Wars. Calls to ban or moderate leather, overt sexuality, and drag from Pride were still ringing into the 1990s (Califia, 1987; Rubin, 2015; S. K. Stein, 2021).

This history aims to tell a small part of that story.

Why Am I Doing This?

A common refrain in the Annual Kink Debate is for young queers to “learn their history.” This is easier said than done: queer history in general is poorly documented, and queer leather even less so. The impact of the AIDS epidemic casts a long shadow in our culture: my friends of that generation lost dozens, even hundreds of friends in the course of a few years. Some are the only surviving members of their leather families. Stories went unwritten or were intentionally omitted from publication. That which was recorded was often not conserved, and those records which were conserved are difficult to access—many are only available as physical copies in research institutions. Limited press runs and anti-obscenity laws further constrained the availability of queer leather texts.

Readers who are curious about the story of kink at Pride have a needle-in-a-haystack problem: while there are histories of leather, of public sexuality, and Pride in general, none (to my knowledge) address their intersection. By assembling disparate texts, I hope to make a hotly-debated and contemporarily relevant history more accessible.

I want to give fellow LGBTQ people—both kinky and vanilla—an understanding of the interplay of queer and leather communities, a grasp of how normative and radical forces interpreted and shaped the expression of Pride, and an appreciation for the people who worked to achieve the culture we have today. I hope that this history gives readers a framework for thinking about leather and Pride in a more nuanced way. As Ellen Broidy, co-organizer of the first NY Pride, put it:

Know your history. Acknowledge the fact that you did not invent this struggle. You can move it forward in new and important ways, but you didn’t invent it.

I say that with a great deal of self-criticism, given my own completely dismissive behavior towards the people who came before me, like the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis, the mainstream homophile organizations of that time. And really they were incredibly brave people. They didn’t participate in the struggle in the way I thought they should have, but at 23 you think you know everything. (Teeman, 2020)

About This Work

I am a gay leatherman. I’ve participated in Pride events since roughly 2008, in cities from Duluth to San Francisco, as well as leather-oriented street fairs like Folsom, Dore, and Folsom Europe. I’ve marched in leather contingents at Pride, and I think they’re a grand old time.

I am not a historian or social scientist. My research methods and theoretical understanding of these issues are amateur at best, and my time limited. I’m citing secondary sources extensively, and what primary sources I have are biased strongly by database availability. There will almost certainly be errors; there are definitely omissions in this text. I’ve attempted to present as much as I can find, but this work is far from complete.

In particular, I’ve chosen to focus on the United States from 1965 to 1995. This is the culture I’m fluent in, and which most of my sources cover. This period covers the origin of Pride, the rise of gay liberation and organized leather, and the partial acceptance of leather within the LGBTQ movement. Much of this work centers on New York and San Francisco—the city which originated Pride, and the city which became a focal point for debate over public displays of variant sexuality. These are the cities for which I have the most extensive sources available. There is more to tell in other cities, but I’m limited by time and access to archives.

This work integrates roughly thirty books, a variety of academic theses and articles, contemporary and retrospective articles, web pages, several hundred periodical issues (including leather, LGBTQ, and general-interest newspapers, magazines, and newsletters), plus archival photography and video footage of Pride. These are mainly drawn from my personal collection, digital archives like the Lesbian Herstory Project, public and university libraries, web pages, and the physical collections of the Leather Archives & Museum in Chicago. I’ve also drawn on my personal experience in leather and at Pride, and conversations with fellow leather people.

For copyright reasons, I’ve avoided reproducing many of the photographs and videos described in this work. Wherever possible I’ve provided links to those media in public archives so you can see them for yourself. Other images are only available in physical formats; see the bibliography for details.

A Note on Terms

Terminology and identity for LGBTQ people has shifted dramatically over the last fifty years, and vicious battles have been fought over the exact meanings and boundaries of words. In particular, readers should know that terms like “transvestite” and “drag” have changed significantly since the 1960s. I urge readers to meet the writers of the past where they were at the time, and to acknowledge their shortcomings while not losing sight of their contributions.

I use a mix of modern senses (e.g. “Pride” for a march/festival, “LGBTQ” or “queer” as a broadly-inclusive group, “trans” to encompass a range of variant gender experiences, and “BDSM,” “kink,” or “leather” to describe a diverse culture of variant sexualities) vs period senses (e.g. “gay liberation,” “sadomasochism,” “S/M,” “transvestite”) when describing a particular person, movement, group, or event. In general, I aim to describe people as they would like to be described, or in a way which includes people who were present but not acknowledged at the time—for example, “LGBTQ activists” instead of “lesbian and gay activists.”

For individuals who have transitioned I use their later names and genders, noting changes when relevant. When describing images of unknown people, I’ve done my best to follow captions, or to code gender and pronouns as I understand their presentation. If I have made any errors, please accept my sincere apologies: I will be happy to correct them.

Structure

This is not a polemic, though I would dearly like to write one as a companion to this work.2 It does not offer a current or complete argument for leather’s presence at Pride. Instead, this work aims to provide the kind of historical context that I think would be useful to a reader who is trying to engage with questions of public sexuality at Pride.

This history begins with some background context about leather as a culture and Pride as an event. It moves on to a thematic sketch which introduces key people, events, and threads of analysis. The bulk of the work is devoted to a mostly-chronological account of LGBTQ and leather activism, Pride, and reactions. It concludes by connecting the historical debate over leather representation with the modern discourse, through the lens of moral panic.

Background

What is Leather?

Part of why the kink-at-Pride debate is so messy is that so few people know what they—or anyone else—means by “kink.” Kink can be read as a simple sexual practice: enjoying spanking, or a fetish for lingerie. However, in this work I’m going to speak of “leather” as a loose umbrella term for kink, BDSM, etc., but with the specific connotation of a queer subculture.3 And leather is specifically a subculture: one with distinct ethics, territory, language, symbols, practices, and technologies. Its recurrent focii are leather, rubber, and various types of “gear,” fetishes, hyper-masculine or -feminine aesthetics, playing with power, the enjoyment of intense sensation, “out-of-the-box” sexual practices, and alternative roles for play, relationships, and social interaction.

As a subculture, leather has its own ethics: an acceptance of variant sexuality, an emphasis on consent, the transmutation of pain into pleasure or emotional catharsis, and a respect for technical skill and experience. It also has its own language, including a rich field of personal archetypes: “top” and “bottom,” “Goddess,” “switch,” “Sir,” “brat,” “girl,” “pup,” etc.4

That language encompasses a broad array of symbols.5 The position of hankies, wallets, and keys may denote one’s interest in giving or receiving an activity. In a practice known as flagging, colors and patterns take on associated meanings: grey for bondage, green for Daddy/boy-style relationships, houndstooth for biting, celery for “just going to brunch.” Collars may denote relational status like a wedding ring, or one’s role as a pup or submissive. Specific types of hats (e.g. “covers,” “boy’s caps”) can indicate one’s preferred position in a power dynamic. Leather vests are frequently decorated with patches and pins to indicate group membership, identity, and interests. Sashes identify titleholders (winners of leather pageants). It is often possible to read a good deal about someone based purely on their outfit.6

Likewise, leather has a richly articulated and endlessly elaborated field of roles and relationship structures, including mentoring & nurturing relationships (e.g. “Daddy/boy”), the complete exchange of power (“Master/slave”), and more playful pack dynamics (“alpha/beta/omega”). Relationships may be sexual or platonic, and last for decades or the duration of a scene. Many emphasize skills-building. These relationships may be diffuse and informal, or organized into leather families. A popular pastime is to draw someone’s network on a cocktail napkin.

Leather has its own stable institutions and cultural events. Bars, clubs, and playspaces provide ongoing physical territory, and street fairs, runs, conferences and contests create temporary sites of leather culture at a campground, street, park, or hotel. When Pride events generate a temporary queer space, they often implicitly create a leather space as well.

As a culture, leather has distinctly articulated practices. These include physical acts like fisting, whipping, rope bondage, suspension in the air, piercing, play with electricity, abrasion, heat, cold, and sensory deprivation. These practices are used in play between leather people in individual or group contexts, transferred during educational classes and mentoring relationships, and performed as art. These practices may be deeply sexual or completely absent of sexual charge: there is no firm boundary. Some people orgasm from being punched in the balls. Ace lesbians can platonically tie up gay men.7

Each of these practices has a highly developed family of sexual technologies which allow that practice to be fun, safe, meaningful, and aesthetically pleasing. There are elaborate techniques for using a single-tail whip and for tying someone up, but also psychological techniques: playing with humiliation, for instance, in a way that is both erotic and ultimately validating. Perhaps the most important of these technologies is the concept of negotiation: a process of discovering what each party is into and what their boundaries are before proceeding to play. Check-ins are frequently integrated into the play itself, allowing partners to ascertain physical and emotional well-being, to offer reassurance, and to continually renegotiate consent. Play itself may be highly structured: a scene may involve negotiation, warmup, rising action, a climactic event, a cooldown, and aftercare which returns participants smoothly and safely to everyday life. Through such a scene sensations, symbols, and roles are carefully—even theatrically—manipulated to create intense, pleasurable, and fulfilling experiences. Scenes vary in intensity and publicness, from a weekend of beatings in a repurposed county jail, to dinner at a fine restaurant where one simply cannot order for oneself.

Other technologies support this play: play parties, for instance, have specific schedules, spaces, and etiquette to ensure everyone has a good time. Separate social and play spaces keep distracting conversation to a minimum and create dedicated contexts for negotiation. Playing in public (e.g. at a bar, club, or street fair) creates safety via community oversight, and in dedicated playspaces, specialized dungeon monitors may limit unsafe scenes. Other safety technologies include safe calls at pre-arranged times when visiting a new partner and reference checks through a loose reputational network. Discussions in the hours and days following a scene allow players to process emotions, to offer feedback, and to deepen bonds.

Some people participate in leather culture thoroughly, and others merely dip in from time to time. Many engage in BDSM independently, incorporating rough play into their sex or day-to-day life without a supporting culture. Some read about pup play on Tumblr and have no idea that any of this exists. Others just like to wear harnesses to circuit parties. There are, again, no absolute boundaries.

What I would like to emphasize here is that leather is more than simply “a kink.” For many, leather is the language in which they are gay: it supports, structures, and enriches their queer sex, love, and family. The public deployment of leather clothing, gear, and practices can be an expression of personal and cultural identity.

What is Pride?

It is tempting to view Pride as a space for universal inclusion and belonging, and Pride is a place which frequently engenders these feelings. But Pride—as a march, a parade, and a festival—is much more than these things. A multitude of agendas, perspectives, and social forces are at play (Dominguez Jr., 1994). Peterson et al. (2018) calls it a polyvocal event: a confluence of diverse people, expressions, and experiences.

Pride is obviously a celebration: there’s cheering, laughing, riotous costumes, music, dance, and no shortage of intoxicants. Participants in modern Pride events report feelings of joy, belonging, and a collective effervescence (McFarland, 2012).8 By bringing together queer people, Pride constructs a powerful experience of collective identity and feelings of pride in one’s LGBTQ nature (McFarland, 2012; Peterson et al., 2018). These feelings were reported at the very first Pride and imbue the event with lasting cultural power (Armstrong & Crage, 2006).

Pride is a commemorative vehicle: it memorializes the Stonewall rebellion in particular and the LGBTQ movement in general. Participants feel connected to history. Pride’s endurance is in part due to its annual nature and the collective rituals of marching and attending (Armstrong & Crage, 2006; McFarland, 2012).

Pride brings together people with diverse experiences, norms, and politics (Taylor, 2014). Trans and intersex people have different concerns than cisgender people. Leather bears and PFLAG moms have very different modes of cultural expression. To be frank, many of us can be insensitive or even cruel to one another. And yet Pride routinely engenders cross-group affinity. Lesbians walk hand-in-hand with gay men, cis people hold up trans-supportive banners, drag queens go arm in arm with leather dykes, and kids howl together with leather pups. McFarland (2012)’s interviews of people at Pride are striking:

None of my participants mentioned negative interactions with other participants….

Some participants felt that transgender people were not fully included in Pride activities. Otherwise I did not find anyone who felt left out of the social experience at Pride. (McFarland, 2012)

Pride is a political protest. Marchers carry signs advocating for specific changes to state policy and cultural norms (McFarland, 2012; Peterson et al., 2018). The participation of politicans, NGOs, corporations, and cishet allies is also a form of political speech (McFarland, 2012). The spectacle of Pride generates media coverage, which amplifies political messaging (Armstrong & Crage, 2006).

Moreover, Pride is also an implicit cultural protest. By making LGBTQ people and their diverse expressions visible en masse, it forces the general public to accomodate queer people and their culture (Taylor, 2014). In a heteronormative culture, queerness ranges from invisible to illegal. Pride creates a bubble of queer norms which opposes these pressures: a counterpublic (Armstrong & Crage, 2006; Peterson et al., 2018; Taylor, 2014). This counterpublic is prefigurative: participants have a chance to temporarily create the culture they wish would exist, and to show it to the world (Peterson et al., 2018).

Pride’s counterpublic creates what many participants refer to as a safe social space (Peterson et al., 2018). Pride is a place to run into old friends and make new ones; to celebrate, to dance, to quietly observe; to blend in or stand out in a space with reduced heteronormative pressures. It is also a place to cruise: to seek partners for play or romance. As Gilbert Baker, inventor of the Pride flag, recalls the first years of San Francisco Pride: “I don’t remember much about my first parades, because I’d go and meet someone right away; then we’d go home and fuck all day” (Hippler, 1985).

For many Pride participants, the culture they wish to manifest includes expanded norms for gender and sexual expression. We embrace our enby aesthetics, dress in outrageous drag, dance on floats in skimpy outfits, bare our breasts or go fully nude. Some hold hands. Some have sex in public. We deploy sexual symbols: suggestive candies, slogans, floats. These displays are not necessarily comfortable for all Pride participants, but they are frequent: McFarland (2012)’s survey of six US Prides in 2010 reported sexual displays at all but Fargo—a town with more reserved cultural norms and a tight-knit community. In this way, Pride functions as more than simply a social space. It is also, as Califia (1991) might put it, a sex zone: a city space where sex is made visible, sought out, and (sometimes) performed. Like cruising spaces in public parks, this sex zone is superimposed on the existing public territory of Pride: one aspect of Pride’s polyvocal expression.

This sex zone can be a form of public expression. As McFarland (2012)’s interviewer asked one lesbian attendee at Burlington Pride: “What does someone walking down the street in leather or walking down the street topless have to do with equal rights? What would be your response to that critique?”

I think that it has to do with self-expression. I think that it has to do with having the right in feeling comfortable expressing themselves in the way that they would like to in an open community, and a Pride Parade seems to be really open and welcoming to people that want to express themselves in that way. (McFarland, 2012)

These visible displays of sexuality are in themselves political statements: visible displays of sexual difference allow queers to claim cultural legitimacy (McFarland, 2012). As McFarland Bruce described in her later work,

By unambiguously showing same-sex desire, Pride participants flaunt the heteronormative cultural standard that makes heterosexuality the only publicly acceptable expression of human sexuality. By summarily rejecting this standard, sexual displays are very much a difference response to heteronormativity. (Bruce, 2016)

Or, as leatherman Bronski (1991) put it:

In a world that functions on sexual repression, the sight of two queens or dykes walking down the street is a vision of the gradual cracking of the social order. The drag queen, the butch lesbian, the clone, the lipstick lesbian, are all expositions of sexual dreams—waking nightmares for the culture at large. Some might be more sexually explicit than others—and not all may be understood by the straight world viewing them—but to consciously present oneself as a (homo)sexual is to grapple with and grab power for oneself.

This is particularly true of the S/M leather scene. The blatant, public image of the leather man (or woman) is an outright threat to the existing, although increasingly dysfunctional, system of gender arrangements and sexual repression under which we have all lived. “This is about power,” we are saying “and the power is ours to do with what we please. It was always ours and we have reclaimed it for our own use and our own pleasure.”

From a political perspective, sexual displays are “a flashpoint for debate over how Pride parades represent LGBT people to the broader world” (Bruce, 2016). McFarland (2012) phrased this conflict in terms of defiant and educational visibility. The defiant perspective deploys sexuality to challenge cultural codes: men kiss other men, women whip one another, and genderqueer people defy binary standards on the street precisely because these acts used to result in social ostracism, arrest, and sex offense charges.

More than creating safe spaces for individuals to resist heteronormative culture through partying and consumption, Pride parades are explicit cultural tools used by the meso-level group of Pride participants to challenge the macro-level construction of queerness as culturally illegitimate deviance. (McFarland, 2012)

The educational perspective emphasizes the similarity of queer people to cishet society through normative displays. It says that there’s nothing implicitly objectionable about queerness, and that Pride’s accurate representation of LGBTQ people as “normal” can change cultural attitudes—ultimately earning civil rights. (McFarland, 2012). Bernstein (2016) described a similar spectrum of strategies in which queer people deploy “identity for critique” to confront social norms vs “identity for education” which builds empathy with broader society. The challenge, as Bruce (2016) elegantly observed, is that educational visibility requires a conservative policing of queer expression in order to depict LGBTQ identity as compatible with mainstream standards of respectability. This requires some participants—for instance, trans and gender non-conforming people, drag queens, and leatherfolk—to suppress important elements of their personal identities in order to make cishet people comfortable.

Of course these perspectives are not exclusive: a single leather contingent can be both confrontationally “out there” and also approachably empathizable, depending on individual dress, displays, and the diverse perspectives of each observer. In allowing contingents and individuals to express a broad range of normative vs variant expressions of gender and sexuality, Pride allows a hybrid of both tactics. (Bruce, 2016).

Public sexual expression isn’t just about reclaiming power and challenging cultural codes. Sexuality is socially constructed: we all start with bodies and instincts, but we learn how to use them. From early childhood cishet culture provides us with images, roles, and scripts for appropriate sexual expression: everything from Disney movies to country songs to Victoria’s Secret billboards provide an elaborate schema for how to live a cisgender, heterosexual, and vanilla life. As M. Altman (1992) summarized a long-standing thread of feminist analysis:

The feminist investigation of sexuality begins with the knowledge that sex as we learn it and live it is not simply “natural,” not simply a matter of biological needs and responses. The way a woman experiences her sexuality, the ways we represent our sexuality to ourselves and enact that representation, are almost impossible to separate from the representations our culture makes available to us. (M. Altman, 1992)

But where does one learn that it is possible to be a leatherman? To be a dyke? To be enby? In order to create our sexual identities for ourselves, we need inspiration from which to draw. We need to see—and more importantly, be able to meet people with a variety of sexualities. As Warner (1999) argues, queer sex is learned: seeing sex is an important part of how we pass on our culture. Our sexual autonomy requires a culture of public sexuality, even though some people may find those images offensive.

The naive belief that sex is simply an inborn instinct still exerts its power, but most gay men and lesbians know that the sex they have was not innate or entirely of their own making, but learned—learned by participating, in scenes of talk as well as of fucking. One learns both the elaborated codes of a subculture, with its rituals and typologies (top/bottom, butch/femme, and so on), but also simply the improvisational nature of unpredicted situations. As queers we do not always share the same tastes or practices, though often enough we learn new pleasures from others. What we do share is an ability to swap stories and learn from them, to enter new scenes not entirely of our own making, to know that in these contexts it is taken for granted that people are different, that one can surprise oneself, that one’s task in the face of unpredicted variations is to recognize the dignity in each person’s way of surviving and playing and creating, to recognize that dignity in this context need not be purchased at the high cost of conformity or self-amputation….

The dominant culture of privacy wants you to lie about this corporeal publicness. It wants you to pretend that your sexuality sprang from your nature alone and found expression solely with your mate, that sexual knowledges neither circulate among others nor accumulate over time in a way that is transmissible. The articulated sexuality of gay men and lesbians is a mode of existence that is simultaneously public—even in its bodily sensations—and extremely intimate. It is now in jeopardy even within the gay movement, as gay men and lesbians are more and more drawn to a moralizing that chimes in with homophobic stereotype, with a wizened utopianism that confuses our maturity with marriage to the law, and perhaps most insidiously of all, with the privatization of sex in the fantasy that mass-mediated belonging could ever substitute for the public world of a sexual culture. (Warner, 1999)

Restrictions on public sex serve, Warner argues, to extinguish sexual culture and enforce distorted hierarchies of acceptable sexuality. To some, two women kissing is a positive example of “love is love”—but a woman tying up her lover is distasteful, degrading, even violent. In many ways, the “no kink at Pride” argument maintains the same sexual hierarchies which Rubin catalogued in her landmark 1982 essay Thinking Sex—for example, by demanding that marginalized sexualities remain private and therefore invisible (Rubin, 1982a).

Debates over the appropriate degree of sexual expression at Pride have been ongoing since the creation of the event. Indeed, it is hard to find an aspect of Pride which has not been a site of contention! As Gerard Koskovich & Sueyoshi (2020) wrote:

Debates about respectability, commercialization, protesting versus partying, and the place of women, drag queens and people of color became inextricably entwined in the implementation of Pride during its first decade. Power struggles, heated exchanges and hurt feelings were perhaps inevitable. The organizers were passionate people navigating their own experiences of trauma and marginalization even as they put together an enormous public gathering that sought to reflect a vastly diverse community. (Gerard Koskovich & Sueyoshi, 2020)

The tension between political-march vs carnival-parade, the debate over sexual expression vs normative displays, how to frame the historical context, and how to balance “a safe space” with broad inclusion of variant groups: these conflicts are arguably inextricable from why Pride works. Griswold (1987) suggests that cultural objects with multiple interpretations have more “cultural power,” and as a polyvocal event Pride has many interpretations indeed. Because of these interpretations, and Pride’s hybrid march/parade/fair format, Pride remains adaptable to many places, cultures, and political moments. We can run different floats each year, choose to be more or less political, more or less sexual. This versatility allows Pride to remain a powerful cultural institution (Armstrong & Crage, 2006).

A Brief Sketch

This history weaves together several themes: the LGBTQ movement more broadly; the development of leather culture, and its integration with the LGBTQ community; the history of young people, sexual displays, and leather at Pride; and finally, the concept of a moral panic. Before we dive into the chronological history, I’d like to offer a brief précis of each of these themes.

The LGBTQ Movement

In the 1960s, the Black civil rights and women’s liberation movements led LGBTQ activists to adopt a more radical stance than the (generally) mild-mannered homophile movement of the postwar era. This emerging activist stance, called gay liberation, engaged in civil protest and constructed an understanding that being “gay” was more than a medical condition or deviant sexual practice, but a distinct, positive cultural identity subject to shared oppression (Weeks, 2016). In response to ongoing police raids of gay bars and other queer spaces, LGBTQ people engaged in a series of violent and non-violent rebellions, including the Stonewall Inn in 1969.

Although it was not the first such event, Stonewall was viewed as a landmark act of resistance, and radical activists organized the first Pride in 1970 to commemorate it (Armstrong & Crage, 2006). Pride was launched as a multi-city event in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, and was adopted in subsequent years by other US cities. Debates over its form and function were frequent, as a microcosm of the debates around gay liberation in general. Regardless, it grew each year and became an increasingly visible symbol of the LGBTQ movement.

During the 1970s an ethos of shared sexual oppression gave way to a proliferation of gay identities grounded in different politics, classes, genders, races, and variant sexualities. In particular trans people, bisexual people, women, and people of color fought for inclusion in decision-making and the recognition of their needs, and advocated for specific political goals in the burgeoning movement (Weeks, 2016).

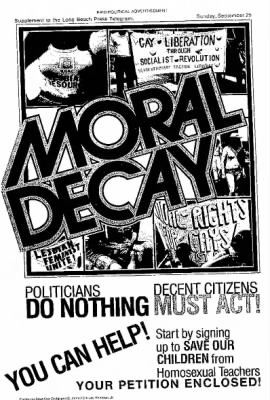

Increased visibility and political organizing led to cultural and policy gains, including city-level nondiscrimination policies for homosexuals. This generated conservative backlash. In 1977 Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign and the Briggs initiative deployed a powerful rhetoric that gays and lesbians were a threat to children, and tried to remove LGBTQ teachers from schools. The religious right adopted the anti-gay charge in earnest by the mid-1980s (Endres, 2009; Rosky, 2021; Side, 1977). These challenges were compounded by the arrival of HIV in 1981, which led conservative politicians to frame gay sex as a threat to public health. Cities moved to close bathhouses and cracked down on sex in bars. The mainstream gay community responded by distancing itself from sexual radicals.

Throughout the 1980s, LGBTQ theorists (and in particular Black feminists) developed sophisticated frameworks for thinking about sex and gender, and their relation to class, race, and power. A complex intersectional analysis arose, and with it an emphasis on pluralism and diversity (Weeks, 2016). As a microcosm of the LGBTQ community, Pride events grew to encompass a broad array of contingents. In 1987 LGBTQ activists organized a massive March on Washington, and ACT UP began a confrontational direct action campaign to end the AIDS crisis (Brown, 2016).

ACT UP’s legacy led to the founding of Queer Nation in 1990, and the development of a coherent queer theory and activist wing of the movement (Brown, 2016). Meanwhile, mainstream lesbian and gay activism grew more institutionalized and increasingly emphasized moderate requests for civil rights—as in the 1993 March on Washington—while leather, bisexual, and trans people continued to push for inclusion in the movement (Warner, 1999).

Young People at Pride

It is tempting for each generation to believe they are the first young people to participate in Pride, and that Pride needs to change in order to become youth-friendly. This is a natural assumption to make: as a young person at Pride, almost everyone there is older than you! Moreover, kids and teens in 2021 experience a much friendlier climate for coming out than generations past—it is reasonable to assume Gen Z’s presence at Pride is unprecedented.

Nevertheless, young people of all ages have participated in Pride events since the early 1970s. Many of the Stonewall Inn’s patrons were teenagers (M. Stein, 2019): New York Times (1969) described “a melee involving about 400 youths” during the Stonewall rebellion, and the Village Voice called some rioters “kids” (Truscott IV, 1969). The first New York Christopher Street Liberation Day in 1970 included groups of teens in the crowd (N. Tucker, 1970), and a 1971 spread from the Advocate shows a small child holding a “Gay Power” sign at the LA parade (The Advocate, 1971a). The next year in New York, straight couples and children waved at marchers from the windows over the Stonewall Inn (Wicker, 1972), and fathers “hoisted their children onto their shoulders” to watch the march (Blumenthal, 1972). In San Francisco, workshops on gay youth and a gay student council meeting were held at Bethany Methodist as a part of 1973 Pride (Bay Area Reporter, 1973b). One 16-year-old named Wendel marched in SF Pride in 1974, and went on to become “a black man on a black Harley wearing black leather” by 1988’s parade. “It hasn’t changed. It’s still great,” he said (Hippler, 1988).

In 1976, two school-age children marched in front of the Eulenspiegel contingent, who carried their banner for S/M liberation (Fink, 1976a). By 1977 flat-bed trailers carried lesbian mothers and their children down the streets of New York City (New York Times, 1977) and kids marched in the “We Are Your Children” contingent in San Francisco; photographs of both parades show babies and toddlers (Crawford Barton, 1977c, 1977b, 1977a; Fink, 1977a). The following year San Francisco’s parade offered organized childcare for marchers, and school-age kids held signs at the parade while others watched (Caroline Barton, 1978; Mendenhall, 1978; Scot, 1978). In 1979, the “Gays Under 21” contingent in SF demanded to have their rights taken seriously by both straight and gay adults, who were “accepting straights’ position that young people have no sexuality,” and “excluding us from the larger gay community” (Gays Under 21 Contingent, 1979).

Adrienne Maldonado was five years old when she marched with her gay dad Santos in San Franciso’s 1985 parade, and she returned in 3 of the next 4 years, declaring it “colorful and nice” (Hippler, 1988). In 1986, Chicago Pride included a parents of gay children contingent, and Rist (1986) describes a family with two small boys, all delighted by a drag queen with a bevy of cock-shaped candies. In SF’s 1988 parade, gay and lesbian parents marched with their children, some in baby carriages (Richards, 1988). The next year, “underaged gay boys and girls from the Billy de Frank Center represented those youth who have early on discovered their gayness and are proud of it” (McMillan, 1989).

In 1991 the “Romper Room” contingent at SF Pride had 30 gay and lesbian youths, ages 15-23 (Greenbaum, 1991). Parents and children made up the 5th contingent at the 1993 March on Washington, followed shortly by a queer youth contingent (The Gay and Lesbian Parents Coalition International, 1993).

While the character and density of youth attendance has shifted, Pride has included people of all ages for 50 years.

Sexual Displays At Pride

The first Pride events in 1970 were generally more conservative than today’s in their displays of sexuality. New York organizer Fred Sargeant recalls “no boys in briefs” at the first NYC Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade (Sargeant, 2010), and video footage of the event shows far more button-downs than bare breasts (Vincenz, 1970).

Nevertheless Bruce (2016) argues that the open expression of sexuality was central to all first Pride marches. Karla Jay of the Radicalesbians said “We wore Halloween costumes, our best drag, tie-dye T-shirts, or almost nothing” at NYC’s 1970 Pride (Kaufman, 2020), and marchers proceeded to Central Park where the Gay Activists Alliance had planned a “gay-in.” As Lahusen (1970) reported, “Gay lovers cuddled and kissed while TV cameras ogled at the open show of gay love.” Participants went naked, cuddled shirtless, and one pair attempted to break the world record for the longest make-out while other attendees debated the “orgy” at the event (Grillo, 1970; Vincenz, 1970). Meanwhile in Los Angeles, the Gay Liberation Front ran an infamous float with a large jar of Vaseline, and topless contestants waved from a convertible (The Advocate, 1970). In the following year’s parade a 35-foot penis-caterpillar careened into a police car causing laughter and applause (The Advocate, 1971b).9

By 1973 San Francisco had gotten into the swing of Pride: the Bay Area Reporter cited “an abundance of male cheesecake” (Bay Area Reporter, 1973a) including a man wearing only a few grapes, and men clad only in towels on the Barracks float (Pennington, 1988). By 1975 San Francisco Pride featured public nudity (M. Owens, 1975) and bare-breasted women on motorcycles (Vector, 1975). In 1976 this bacchanal atmosphere reached new heights. Women and men went nude in the heat, and Jim Gordon stood “stark naked at Castro and Market” before boarding a bus he described as “an orgy” (Berlandt, 1982). The celebration in Marx Meadows featured “rampant nudity” (Pennington, 1988)—“EVERYONE stripped to their most comfortable level; and there was much hugging, kissing, and squeezing” (Hardman, 1976).

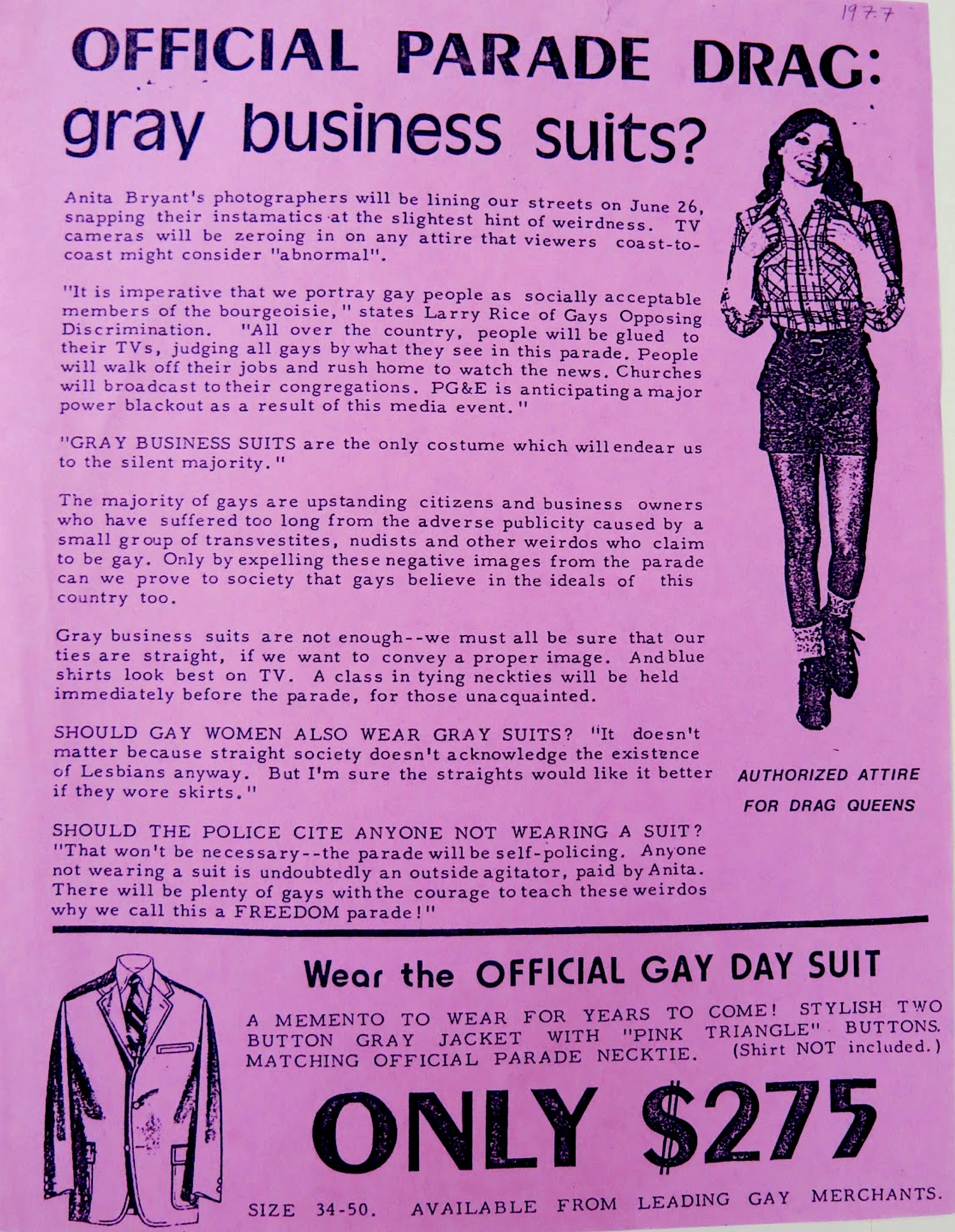

In 1977 Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children campaign deployed footage of San Francisco’s indiscretions (Pennington, 1988), claiming that San Francisco was “a cesspool of sexual perversion gone rampant” (Pettit, 1977c). Parade organizers reacted to homophobic backlash by banning nudity and other “negative imagery” in 1977 (Pettit, 1977b), which led to a considerably more buttoned-down parade (Associated Press, 1977). Despite the ban and threats by parade monitors to involve police if people refused to wear clothes, 1978 featured “about ten bare-breasted women” (Mendenhall, 1978), men in very short shorts and lamé bikinis, as well as “a semi-naked man roller-skating past the camera with considerable aplomb, wearing only knee pads, a thong and butterfly wings” (KPIX, 1978).

By 1980 a sense that Pride was too political, coupled with a drop in attendance, led co-chair Bruce Goranson to declare that San Francisco Pride needed to reach out to drag, women, leather, and the business community. The nudity ban appears to have held for several years (Berlandt, 1982; Gay Freedom Day Committee, 1980) but in 1980 and 1983 San Francisco police ignored “partial nudity” and at least one “totally naked” man (Spunberg, 1983; Sun, 1980). Elderly women in New York City watched shirtless men in shorts pass by and commented on “so many naked people” (Clendinen, 1981). By 1986 Chicago’s parade included “drag, leather, and near-nudity” (Rist, 1986), and in 1989, San Francisco’s “Sexuality was proudly and boldly represented” by scantily clad porn stars in convertibles, many bare-chested men (and occasional women), and completely naked Dykes on Bikes (McMillan, 1989; A. White, 1989). New York police looked aside in 1991 as lesbian marchers removed their blouses and T-shirts, and one man wore only a white jockstrap and matching ostrich feather headdress (United Press International, 1991).

In 1992, an impromptu block party in San Francisco’s gayborhood featured two men who danced, showed hole, and sucked each other off while perched on top of a newspaper stand. Their audience consisted of “wall-to-wall people clapping and cheering,” others who tried to jump up and join in, and a family “watching with their mouths open in disbelief.” The next day at the parade, some Dykes on Bikes rode bare-breasted, and one fist-fucked an inflatable sex doll (Martin, 1992).

Video of Dallas’ 1993 Pride shows floats with masculine figures in bikinis and women’s swimsuits, and no shortage of shirtless men (some in Daisy Dukes) in the crowd (Bucher, 1993). In 1993, San Francisco’s Radical Faeries marched nude (Provenzano, 1994a) and New York women marched with bare breasts and dildos. At Castro Street Fair that same year, police were “everywhere” to prevent public nudity, and accosted four nude walkers (Barnes, 1994). In 1995, New York’s AIDS Prevention League had a flatbed trailer where “four men clad only in briefs simulated various sex acts, some quite graphically” (Dunlap, 1995).

A Brief History of Leather

The origins of gay leather in the United States are somewhat unclear, but popular accounts discuss a wave of gay men who were discharged from the military following World War II, combined with a rebellious, masculine image of black-clad motorcycle gangs in the 1950s (Addison, 2012). Gay men organized their own motorcycle clubs (which sometimes, but not always, included a BDSM component) and formed S/M clubs in the 1950s and 1960s—but these organizations were largely secretive (Clark, 1996a). In the 1960s S/M fashion and image became more widespread: D. Stein (1991a) indicates that experienced S/M players withdrew to more insular, established circles. On the other hand, Clark (1995) asserts that by 1969, New York’s “leather men lived and worked in good and bad neighborhoods… they went to leather bars, and some belonged to leather, S/M, or motorcycle clubs.”

Like mainstream gay bars, leather bars and baths were targets of police harassment—sometimes violent (Armstrong & Crage, 2006; S. K. Stein, 2021). The LAPD raided the Black Cat in 1967 (beating patrons and rupturing one bartender’s spleen), a Homophile Effort for Legal Protection fundraiser at the Black Pipe in 1972, and the Mark IV baths “slave auction” fundraiser for gay charities in 1976: an effort which involved roughly a hundred officers, two helicopters, a dozen vehicles (Los Angeles Leather History, 2021; Rubin, 1982b; S. K. Stein, 2021). In 1978, San Francisco’s vice squad conducted an extensive harassment campaign against South of Market leather bars (Califia, 1987).

The development of a coherent leather community and political identity trailed gay liberation by roughly a decade. Per Rubin (2015),

… SM was far less institutionally developed than was homosexuality. Communities were relatively unstructured, and personal identifications as sadomasochists or fetishists were rarely as common or as well established as were those of homosexual men and women…. it took longer for a significant number of sadomasochists (straight and gay alike) to start perceiving themselves as an oppressed minority rather than as people with a psychological condition. In the US, that transformation, the reconfiguration of personal problems as political ones, occurred primarily in the 1970s. (Rubin, 2015)

That transformation required institutions and media for cultural exchange: kinky people had to talk to one another. In 1970 Pat Bond and Terry Kolb founded The Eulenspiegel Society (TES) to promote education, social gatherings, and political advocacy for straight and queer people into BDSM. As with gay liberation, TES drew on previous social movements to develop a political language for SM, and repositioned SM as a sexual minority identity (Green, 2021; Rubin, 2015). San Francisco’s Society of Janus (another mixed-orientation group) followed suit in 1974, and an increasing number of queer people began to come out as kinky (Rubin, 2015).

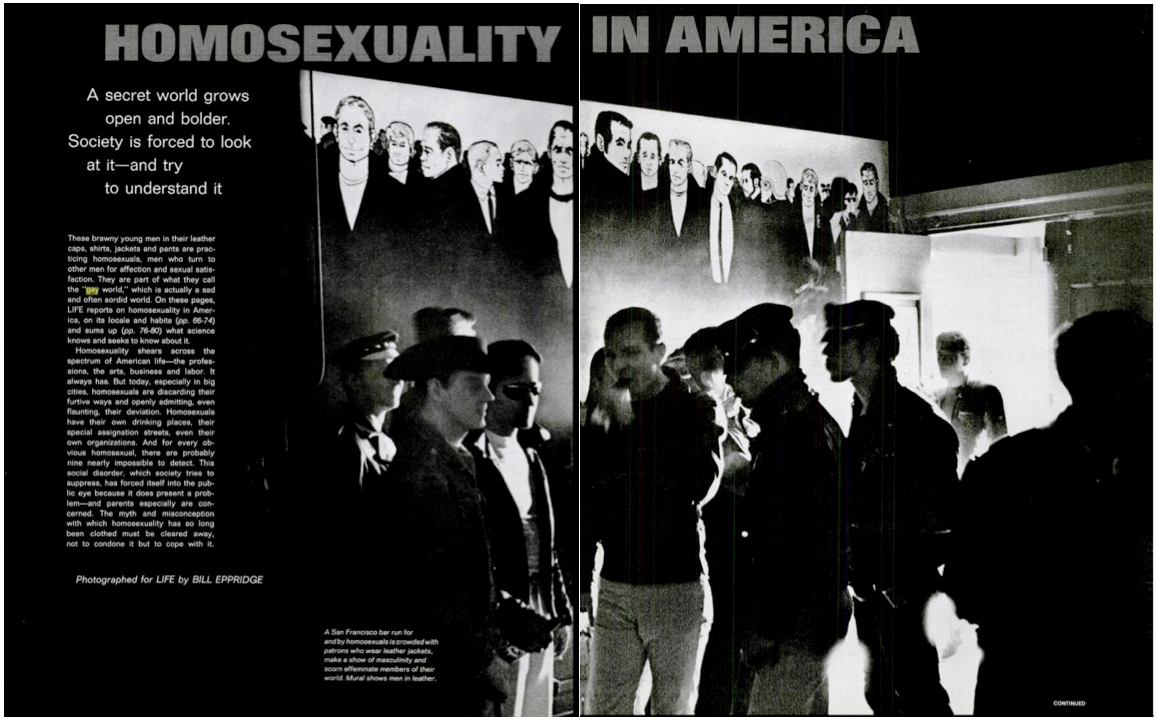

Increased visibility led some lesbian and gay leaders to “normalize” the gay community by excluding BDSM (S. K. Stein, 2021). In the early 70s, Kantrowitz (1989) says, “gays asked leathermen and drag queens to wait” until “more important issues were dealt with.” S/M was especially threatening to the feminist and lesbian movements of the 1960s and 1970s, who often considered the practice a violent reflection of patriarchal domination (Califia, 1987). In 1978 San Francisco lesbians founded Samois, which melded The Eulenspiegel Society’s political creed with lesbian feminism. The conflict between Samois and the anti-porn, anti-S/M group Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media (WAVPM) became a major front in the Lesbian Sex Wars (Rubin, 2015). Meanwhile, popular media represented leather sexuality as a seedy underbelly of gay life. The 1977 “Save Our Children” campaign and documentaries like CBS’s 1980 Gay Power, Gay Politics equated homosexuality with sadomasochism and characterized S/M as violent, nonconsenusal, and morally corrupt. In response, lesbian and gay leaders sought to reposition the movement as a narrow interest group rather than a demand for broader sexual liberation (Bernstein, 2016).

Citing distorted media bigotry, fagbashing, and “the oppression of our lifestyle within the larger gay/lesbian community,” Brian O’Dell founded New York’s Gay Male S/M Activists (GMSMA) in 1980, and the Lesbian Sex Mafia (LSM), a New York lesbian S/M group, was founded the following year (Rubin, 2015). City-scale S/M organizations proliferated and converged on a message that S/M activities could and should be consensual, non-exploitative, and safe (S. K. Stein, 2021). Leather periodicals flourished and leather bars ran increasingly popular “titles”: pageants featuring fetishwear, interviews, and fantasy skits. In the second half of the 1980s, leather titleholders began to play increasingly political roles as fundraisers, organizers, and writers (S. K. Stein, 2021).

In response to the AIDS crisis, straight and LGBTQ society alike often blamed leather people. “The fisters caused this crisis,” recalls Rofes (1991). “Kinky men with extreme sexuality are getting their due.” Leather remained a mark of stigma for many LGBTQ people, and police raids continued. Mr. Marcus (1986) described police harassment of “leather fags” in San Francisco, LAPD conducted a series of raids of leather bars in 1988 (Los Angeles Leather History, 2021), and in 1987 Operation Spanner began in Britain: an effort which would detain hundreds of gay men and charge dozens of consensual players with “assault” and “unlawful wounding”—16 were convicted and eight imprisoned (S. K. Stein, 2021). Nevertheless, by the end of the 1980s leather activists had achieved major gains: formal inclusion in the 1987 March on Washington (B. Douglas, 1995b), seats at the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force’s Creating Change conferences, and the formation of national-scale political networks like the all-gender, all-orientation National Leather Association (Rubin, 2015).

By the early 1990s, leatherfolk had developed a thriving press including written and visual erotica, how-to manuals on technique and safety, and political argument—often combined in the same magazine. In 1991, Chuck Renslow and Tony DeBlase founded the Leather Archives and Museum to conserve leather culture (including many of the sources for this essay). Despite continued arguments from normative lesbian and gay activists who wanted to exclude drag and leather from the movement (S. K. Stein, 2021), national-scale organizing continued through the 1993 March on Washington (The Gay and Lesbian Parents Coalition International, 1993). Police harassment faded in the 1990s: Boston police arrested three organizers of the Thunderheads Christmas Party in 1991 (S. K. Stein, 2021) and the LAPD raided the Dragonfly in 1993 (Feldwebel, 1994). S. K. Stein (2021) states that no major BDSM organization faced criminal charges after 1999.

Leather In Support of Queer Life

If Pride is understood in part as a commemorative vehicle which honors the history of the LGBTQ movement, then a part of leather’s cultural legitimacy at Pride stems from leather’s contributions to that movement. Despite opposition, queer leather people and organizations worked to support the broader cause of queer rights: organizing political actions, building spaces for queer centers, supporting people with AIDS, and raising money for Pride events.

Leather people were involved in the organization of, and participated in, the very first Pride parades. For example, Leatherman Peter Fiske frequented the Stonewall Inn, was at the Compton’s Cafeteria riot in 1966, and marched in the first San Francisco Gay Freedom Day in 1970 wearing a leather vest and chaps (Teeman, 2020).

Bisexual leatherwoman Brenda Howard is often referred to as “the mother of Pride”; Limoncelli (2005) states she coordinated a rally honoring Stonewall one month after the riots, and L. Nelson (2005) claims she originated the idea of Pride Week and was a member of the Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee in the 1970s and 1980s. Although members of New York’s Gay Liberation Front contest claims of her centrality in Pride’s origins (San Francisco Bay Times, 2021), there is documentation of her marching in the 1980s (Unknown, 1980s, 1987) and serving on the organizing committee for the 1987 March on Washington (S/M-Leather Contingent, 1987). Limoncelli (2005) also claims she advocated for the inclusion of “bisexual” in the title of the 1993 March on Washington, and worked on the Stonewall 25 march in 1994. While leather people sometimes downplayed their S/M interests to remain palatable to a broader LGBTQ community, Howard marched in leather contingents wearing gear. The photograph commonly used in biographies of Howard is actually a crop of a larger image, which reveals that she was marching under The Eulenspiegel Society’s banner next to Lenny and Sharon Waller—the manager of New York’s Hellfire club, the Vault, and Manhole. She appears to be clipped to the person next to her via a leather lead (Unknown, 1980s).

Reverend and leatherman Troy Perry served as one of three chief organizers for the first Los Angeles Pride, and was arrested for leading a protest fast after the parade. In January of 1970, Perry had officiated a wedding ceremony for two lesbians (Warner, 1999), led 250 homosexuals in a march for police reform in LA (Los Angeles Leather History, 2021), and a hunger action on the steps of the LA Federal Building for gay rights (Los Angeles Leather History, 2021). In 1971, Perry led a march from Oakland to Sacramento (nearly 100 miles away) to support Willie Brown’s consenting adults bill (Pennington, 1988). He also spoke at the 1979 March on Washington (National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, 1979). Perry founded the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), which you may know from their supportive presence in Pride events around the world. MCC continues to be both queer- and leather-friendly to this day.

Larry Townsend, author of The Leatherman’s Handbook, founded the Homophile Effort for Legal Protection (HELP) in 1969 (Fritscher, 2009) and was arrested during its monthly fundraiser at The Black Pipe in 1972 (Los Angeles Leather History, 2021). He also founded the Hollywood Hills Democratic Club: possibly the earliest openly gay democratic club (Los Angeles Leather History, 2021). Morris Kight, another of the organizers of the first LA Pride and founder of LA’s Gay Community Services Center, volunteered to be auctioned off as a leather “slave” for a day in 1976 (Humphries, 1976).

Eric E. Rofes was one of the organizers of the 1979 March on Washington (Rofes, 1991), and went on to work at community centers in the 1980s. Cookie Andrews-Hunt, leather historian and co-founder of the National Leather Association, helped organize the 1987 and 199310 marches on Washington, as well as Stonewall 25. Leather people also participated in direct actions: in 1989, Jim Kelly was arrested for blocking traffic during an ACT-UP sit-down demonstration which called for AIDS funding (GMSMA, 1989a).

In 1983—before the age of corporate Pride sponsorship—New York Pride experienced a budget crisis. New York’s leather community responded by throwing a fundraiser at a prominent leather bar (P. Douglas, 1995). Through bootblacking, auctions, raffles, and flea markets of leather gear and erotica, they raised enough money to ensure that Pride happened the following year (EDGE Media Network, 2015; GMSMA, 1987). By 1985 Leather Pride Night (LPN) contributed a sixth of NY Pride’s budget (D. Stein, 1985), and in 1987, Heritage of Pride (HOP) remarked that LPN “raised more money for the New York march and rally than any other event HOP has been involved with” (GMSMA, 1987)—a relationship which continued well into the 2000s (EDGE Media Network, 2015; GMSMA, 1990a). LPN raised more than $350,000 over the next three decades for NY Pride, GLAAD, community centers, AIDS assistance, queer youth, and more (EDGE Media Network, 2015; Leather Pride Night, 1996). Jo Arnone, co-founder of the Lesbian Sex Mafia and regular auctioneer at LPN, went on to help raise over a million dollars for leather, LGBTQ, and other charitable organizations (Arnone, 2020). Leather Pride Nights sprung up in other cities as well (Street, 2018).

When the newly-founded Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center denied access to Gay Male S/M Activists (GMSMA), GMSMA President Richard Hocutt confronted the Center’s board at a public hearing and won crowd support for the inclusion of the leather community (P. Douglas, 1995). GMSMA volunteers rehabilitated space for the Center, donated chairs, and later offered significant financial support (D. Stein, 1985). By 1989, contests like Mr. Leather New York were raising as much as $20,000/year to support the Center (GMSMA, 1989c).

In San Francisco, leather bars and baths were major sponsors of Pride. SF leathermen like George D. Burgess founded the AIDS Emergency Fund (AEF), which provided direct assistance to people with AIDS (Mr. Marcus, 1990a), and Mr. S Leather’s Alan Selby ran fundraising for the organization (A. White, 1985). By 1985 titleholders like Patrick Toner (International Mr. Leather 1985) were regularly hosting AIDS benefits, and AIDS fundraisers were regular fixtures at leather bars like Chaps: a single weekend could raise as much as $7,000 through spanking, paddling, and raffling off gear (Mr. Marcus, 1985a). In the early 1990s, bare-assed leatherfolk began marching to raise money for AEF (Mr. Marcus, 1992a).11 By the mid-1990s, leather bars were major fundraising sites: Mr. Marcus (1994) remarked that the San Francisco Eagle’s “outrageous” fundraisers had generated millions of dollars for AIDS and other queer causes. In 1992, San Francisco’s LeatherWalk featured bare-assed kinksters in gear marching down city streets to raise money for the AIDS Emergency Fund (Mr. Marcus, 1992a); the event became an annual institution.

Leather people also served as Pride organizers and marshals. By 1984 GMSMA had three members on New York’s Pride committee (GMSMA, 1984). Jo Arnone announced New York Pride in 1985 (Arnone, 2020). After years of work in previous Pride parades, Helen Ruvelas (of International Ms. Leather’s (IMsL) steering committee) served as co-chair of the parade committee in 1986 (Rein, 1986). Zach Long (Leather Daddy V 1987) served on the board of the Larkin Street Youth Center, worked for the AIDS Healthcare foundation, and served as SF Pride’s parade marshal in 1990 (Bay Area Reporter, 1991; Mr. Marcus, 1990b). Shadow Morton, a trans man and the co-founder of International Ms. Leather, co-chaired SF Pride in 1995 (Bradley, 1995). Pat Baillie (International Ms. Leather 1995 and president of the IMsL foundation) went on to serve as co-president of Albequerque Gay Pride in 2006 (IMsL Foundation, n.d.).

At the national scale, leather people were explicitly included in queer organizing efforts by the late 1980s. In 1986 GMSMA sent members to early meetings on whether to hold an LGBTQ March on Washington, which led Brenda Howard (representing LSM) and Barry Douglas (representing GMSMA) to co-chair the march’s S/M contingent (B. Douglas, 1995b; Limoncelli, 2005; S/M-Leather Contingent, 1987). Leatherwoman Peri Jude Radecic served as legislative and executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (B. Douglas, 1995b), and leatherman Ivo Dominguez, Jr. served on its board (Dominguez Jr., 1994). The NGLTF’s Creating Change conferences included leather panels, and leather people in full gear joined the NGLTF in meeting with the National Endowment for the Arts to discuss right-wing censorship of queer art. (B. Douglas, 1989, 1992; NGLTF, 1991).

Leather at Pride

As a high-visibility event which represented queer people to the world at large, Pride served as a focal point for arguments over leather’s place in the LGBTQ movement. While leather-wearing motorcycle clubs and kinky people in leather gear participated in the earliest Prides (Hardy, 2003b; Teeman, 2020; The Advocate, 1970) explicitly S/M-focused contingents did not (to my knowledge) appear until 1972 (Fink, 1972a; Green, 2021). Their presence in parades was fiercely debated in the late 1970s, when San Francisco Pride attempted to ban BDSM imagery and leather clothing from the parade (Califia, 1987). By the mid-1980s leather and visible S/M groups were a regular fixture of Pride parades in New York and San Francisco, where they have remained ever since. However, Pride’s inclusion of leather and drag remained targets of criticism: the right viewed them as symbols of queer people’s depravity (Institute for the Scientific Investigation of Sexuality, 1985), and some LGBTQ people positioned leather and drag as impediments to mainstream acceptance (Kirk & Madsen, 1989; S. K. Stein, 2021; W. Tucker, 1983). Just as LGBTQ leaders cautioned pride participants to tone down variant displays, some leather leaders called members of their own community to exercise discretion—while others asserted the importance of exuberant expression.

Cycle MC (a NYC gay motorcycle club) participated in New York’s first Pride parade in 1970 (Hardy, 2003b; Los Angeles Leather History, 2021), and a leather-clad motorcycle brigade rode Harleys in Los Angeles that same year, which “tended to shock straight spectators into silence” (The Advocate, 1970). However, motorcycle clubs did not necessarily participate in S/M or represent it to the public. Some leather individuals did wear gear to early Pride events. Peter Fiske marched in chaps and vest in San Francisco, 1970 (Teeman, 2020). The earliest record I have of an S/M-focused Pride contingent is from New York, 1972, when The Eulenspiegel Society carried a banner reading “Freedom for Sexual Minorities” in NY (Fink, 1972a). The following year, the Gold Coast leather bar marched in Chicago. Their float included a classic car featuring a leather “Bonnie and Clyde,” followed by a huge black leather boot with chains, along with over a dozen leathermen (Dunfee, 1973).

In 1974, leatherman Doric Wilson marched in a leather vest with his mother in New York, while one woman sported aviators, bra, short shorts, knee-high boots, and a singletail whip astride her bicycle (Fink, 1974a). Others flagged and wore leather collars on leads (Fink, 1974b).

A letter to the Bay Area Reporter complained about the sight of “slaves on chains, licking grime off their master’s boots, in full view of 50,000 people,” at San Francisco Pride in 1975, and demanded a “responsible parade” of “real gays” (Joplin, 1976). By 1976, leathermen were parading down the streets of New York with whips on display, and being led cuffed and chained by leashes (Fink, 1976b). In 1977 Chicago Pride was led by a color guard of men in leather (Associated Press, 1977), and Midland Link Motor Sports Club “played a founding role in organizing” Birmingham Pride (Bishopsgate Institute, n.d.). Despite calls to tone it down after the extravagance of 1976, leather was well-represented in SF’s 1977 parade: leather columnist Mr. Marcus (1977a) was pleased to see bikers, leather men and women, and South of Market clubs in the parade, but emphasized the need for participants to avoid “flaunting their sexuality.”

I hope to see the bikers, and the leather men and the cowboys and levi men. And I hope and pray you will remain calm, peaceful, and for once not try to be outrageous, overly campy or cause anyone embarrassment or shame. This is OUR national pride day. This is our chance to raise the consciousness of many people who are ambivalent about Gay Human Rights. Don’t blow it! Make San Francisco’s straights PROUD of their Gay population…. (Mr. Marcus, 1977b)

1978 marked San Francisco Pride’s first entry of an explicitly SM-focused organization as opposed to bars or baths. The Society of Janus marched joined by members of Samois, a lesbian S/M group. Their contingent included a red Jeep with a woman chained to the front, and lesbians marched bearing visible whip marks. Patrick (then Pat) Califia, co-coordinator of Samois, recalled jeering, spitting, and shouts of “Nazis” from the crowd. Despite Janus having a permit from the Pride committee, Pride monitors attempted to expel the contingent on the basis that it violated regulations against “images that were sexist or depicted violence against women” (Califia, 1987). The SF Chronicle ran a large photograph of the Janus contingent (Mendenhall, 1978), and Priscilla Alexandra compared them to Nazis in the Bay Times (Califia, 1987).

When Samois applied for a permit for 1979’s Pride, the parade committee attempted to pass a regulation banning the wearing of leather and S/M regalia by participants, with police enforcement if necessary (Califia, 1979, 1987). Samois members responded by joining the March subcommittee, organizing a leaflet campaign, and ultimately passing regulation supporting the freedom of Pride attendees to wear whatever they wanted (Bay Area Reporter, 1979; Califia, 1987). However, S. K. Stein (2021) writes that SM contingents in San Francisco faced recurrent attempts to ban their participation over the next six years.

Despite this opposition Samois marched in 1979 and 1981, and distributed their literature at the festivals afterwards. The Society of Janus continued to march as well. Califia (1987) recalls that that crowds grew friendlier, “although we still got hissed and booed occasionally,” and the majority of their membership still felt it was unwise to march. Meanwhile Jo Arnone (co-founder of the Lesbian Sex Mafia) marched in full leathers in New York’s 1979 Pride (Arnone, 2020), and the New York Times recorded that “the leather-jacketed marchers of the Eulenspiegel Society, which advocates sadomasochistic relationships” was among those contingents receiving the loudest cheers (New York Times, 1979). In Miami, the Thebans motorycle club led the parade “dressed in the usual apparel” (Histo, 1979).

1979 also occasioned a major LGBTQ march on Washington, DC. Leatherman Eric E. Rofes helped organize the event (Rofes, 1991), and Troy Perry spoke (National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, 1979). Despite Alan Young’s welcome message highlighting the broad diversity of queers (including “those who bite and those who cuddle”) (National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, 1979), leather participation was banned from the march (S. K. Stein, 2021). Rofes (1991) recalls a fellow organizer demanding marchers remove their handcuffs because of local regulations.

In the 1980s leather clothing and S/M gear became staples of Pride parades. In 1981 GMSMA began marching in NYC (though they faced “initial opposition” per S. K. Stein (2021)), and they fielded increasingly visible contingents each following year (GMSMA, 1984). New York marchers wore “leather and chains” (Clendinen, 1981). In San Francisco, photographs of Pride show leather people of all genders wearing chaps, vests, arm and wrist bands (A. White, 1982), or studded “Mister & Mistress” collars (Hicks, 1982). Some smaller Prides, like Santa Cruz, included leather “contingents” as small as one person (Reporter, 1992). Photographs of NY Pride in 1983 show women in full leather with collars (Unknown, 1983a), floggers, handcuffs, and padlocks (Unknown, 1983b). In San Francisco, titleholders rode in South of Market contingents (Stewart, 1983), and wore vests, collars, and chaps (Rink, 1983). One “straight sympathizer” wrote to the Bay Area Reporter complaining of the “sexual circus” at Pride: “all they saw was tit clamps and campy drag, chains and leather, and embarrassing public displays of eroticism”—to which the BAR replied “Take the sex out of sexual liberation and there’s no liberation” (W. Tucker, 1983).

By 1984 the Lesbian Sex Mafia (LSM) joined GMSMA at New York Pride, and marchers wore leather chaps, vests, and harnesses with cock-straps running down into their shorts (GMSMA, 1984; D. Stein, 1985; Unknown, 1985). San Francisco’s parades featured industrial tow-trucks bearing leathermen hanging from the back in “slings” and tossing flowers to the crowd (Stewart, 1984). 1984 also saw the first Folsom Street Fair: a public BDSM-oriented event which helped convince Pride officials that leather participation was OK (S. K. Stein, 2021). By 1986 the Society of Janus, the Outcasts (a lesbian S/M group) and the 15 Association (a gay male S/M group) joined forces in an official S/M community contingent (Rubin, 2015), fielding more than a hundred marchers and running a booth at Civic Center plaza (Bay Area SM Community, 1986, 1987).

At the March on Washington in 1987, roughly 700 leather people from around the country marched wearing “lots of leather” in the S/M-Leather contingent, to cheers from spectators (B. Douglas, 1987; Hardy, 2003a; S. K. Stein, 2021). Video shows raucous applause, leather in abundance, and multiple marchers leading one another on leashes—among them Brenda Howard herself (Unknown, 1987).

In 1987 San Francisco’s leather community encouraged marchers to join them wearing “your hottest gear,” and fielded the Precision Drill Whip Team, which performed synchronized whip demonstrations—a Pride tradition which continues to this day (Bay Area SM Community, 1987). Following them was leather bar Powerhouse, whose float was “covered with writhing, dancing men partially dressed in black leather chaps and armbands” (Linebarger, 1987). Leather was an increasingly integrated part of public queer life: the Society of Janus’ erotic art exhibition at Castro Street Fair drew “a big crowd” that year (Mr. Marcus, 1987b), and Urania (1987) reported “a great cheering section” and “lots of wonderful support” for New York’s leather contingent. In Seattle, leather people marched in chaps, harnesses, and nipple clamps (G. Nelson, circa 1987-1988b). One photo shows a man in cutoff shorts and nipple clamps in an elaborate rope harness serving as as an anchor for a cluster of helium balloons (G. Nelson, circa 1987-1988a). The following year, the Editrix of Bound and Determined rode with her motorcycle club, The Sirens, in NYC—“literally cracking her bullwhip as she rode” (Bound & Determined, 1988). Leather-clad S/M dykes also marched in London (Disgrace, 1988b, 1988a).

Despite increasing acceptance, calls to reduce or remove drag and leather participation from parades continued. Laura L. Warren’s letter to the BAR complained that such displays hindered acceptance:

I think we will all get a lot further in the area of gay rights if we show that we are not a lot of freaky people waving wands and wearing funny clothes, that we are all normal people who simply want to lead a normal life. (McMillan, 1988)

To this, McMillan (1988) responded:

So you see, it was a group of “freaky people wearing funny clothes” back then who made it possible for you and me today to sit undisturbed, sipping cocktails in the bars of our choice… We are most emphatically not, for love and life, going back. We are not going to act or dress or speak the way with which the majority of straight society might feel comfortable. (McMillan, 1988)

Others like McPherson (1988) noted that their initial discomfort with leather, S/M, and drag participation had faded as they learned more about those subcultures, and that they now found those displays a valuable form of playful self-expression.

In 1989 the S/M-Leather contingent was one of the largest in New York’s march (GMSMA, 1989d; D. Stein, 1991b). Los Angeles’s largest contingent in 1990 was the National Leather Association, which fielded more than 400 people over two city blocks (Los Angeles Leather History, 2021). B. Marcus (1989) wrote “we are now warmly welcomed by most participants,” though many leather people still avoided marching for fear of losing their jobs, family, or friends. Indeed, S. Carlin Long marched in GMSMA’s contingent in 1992, was spotted by co-workers, and fired the next morning (Long, 1992).

While S. K. Stein (2021) argues that parade organizers in the early 1990s mostly discouraged BDSM marchers from displaying whips and chains, or engaging in overt BDSM displays, and while Memphis went so far as to ban minors from any event even describing sadomasochism (not to mention homosexuality!) (O’Neill, 1990), San Francisco continued to embrace leather. Photographs of 1989 Pride show a whipping scene in front of houses in the parade assembly area (Jur, 1989a) and at least one marcher in the leather contingent showed off a jockstrap (Jur, 1989b). The Pride festival at Civic Center included a “leather stage” in 1989 and 1990 (Mr. Marcus, 1989a, 1990b) as well as booths by the National Leather Association and Drummer Magazine, where Mr. Marcus (1990b) says one could see demonstrations of bondage and piercing. Meanwhile, marchers with Seattle Men of Leather wore codpieces and harnesses (G. Nelson, Circa 1990), and Chicago Pride featured large leather contingents (S. K. Stein, 2021). In Dallas, video of the 1992 and 1993 Pride parades shows wild applause for their leather contingents, led by singletail whip displays (Bucher, 1992, 1993; NLA: Houston, 1993). Leather floats in San Francisco received “loud applause” in 1992 (Mr. Marcus, 1992b).

As 1993’s March on Washington approached, leatherwoman Brenda Howard advocated for the inclusion of “bisexual” in the title of the march (Limoncelli, 2005), and GMSMA and other leather organizations constructed a political platform for the S/M contingent (B. Douglas, 1992). The S/M-Leather contingent included marchers in short shorts and gear (Dubois, 2014). “All along the march route, the crowds cheered and applauded the leather men and women that made the trek through the streets of our capital” wrote an ebullient Mr. Marcus (1993). Tala Brandeis, a trans dyke from San Francisco, entertained the contingent with whip demonstrations, raising blood through the shirts of some bottoms (Califia, 1994b).

As usual, the religious right used these displays to drum up opposition for LGBTQ rights. 1993’s “The Gay Agenda” used footage of San Francisco Pride, including “scantily clad men in chain-mail G-strings and leather” to drum up opposition for LGBTQ military service in Washington D.C., and to build support for anti-gay propositions in Oregon and Colorado (Conley, 1993; O’Neill, 1993). A chorus of normalizing queer writers like Bruce Bawer were upset by sexual displays, drag queens, and bondage as a public aspect of LGBTQ life (Bawer, 1993), or blamed drag and leather for reinforcing anti-gay stereotypes (Kustin, 1993). Indeed, March on Washington organizers—concerned about the public-relations impact of associating the movement with sadomasochism—refused to show images of the leather contingent in press releases, video, or discussions (Califia, 1994b).