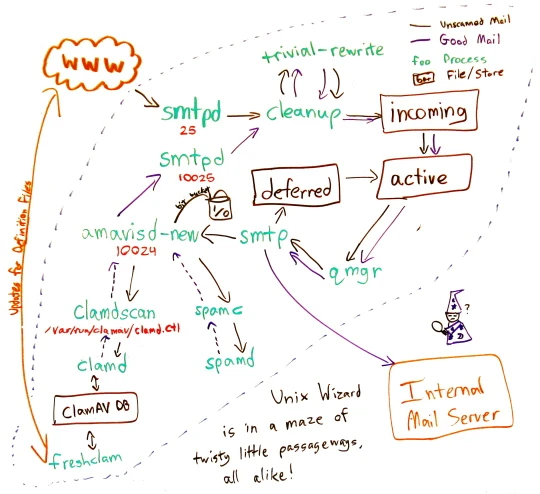

This week, I spent a long time mucking about in the mail relays. Freshclam skipped over 8 of the 9 mirrors it knew about, and the remaining one was down, so it spun for an hour trying to fetch new virus definitions. While it was busy with that, clamd woke up, tried to refresh the database, couldn’t acquire the lock (since freshclam had it), and shut itself down. That broke the two clamdscan processes that amavisd-new was using, and 6000 messages piled up in the Postfix incoming queue. I managed to get the whole mess resolved with the help of debian-volatile, which provides rolling stable packages for ClamAV and other frequently-changing projects. I also put in place more comprehensive monitoring for Cacti and Nagios, so next time the queues explode, we’ll know about it sooner.

The upgrade to ClamAV prompted me to go through and fix all of amavisd-new, including making it talk to SpamAssassin again. The upside is that all incoming mail is now thoroughly filtered for spam and viruses before hitting our Exchange servers, which really cuts down on load and junk in people’s inboxes.

For the last few days, I’ve been drawing little sketches on my whiteboard, regarding the various goings-on at work. My boss Laird suggested that I put them online, so here they are!

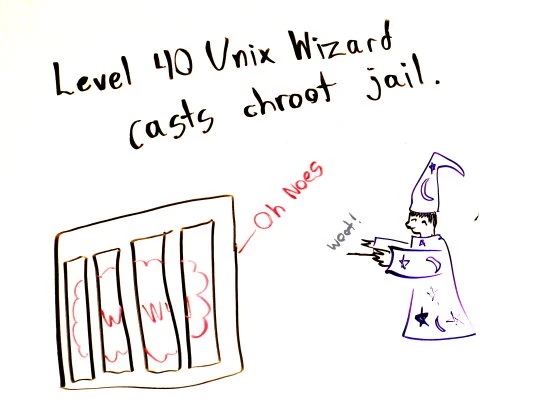

On Tuesday, I was fixing the file transfer box; an apt upgrade had updated some libraries that SFTP relied on, which meant rebuilding the chroot environment with the help of ldd.

It looks like there’s a catastrophic memory leak in the Rails app I wrote last summer, and in trying to track it down, I needed a way to look at process memory use over time. So, I put together this little library, LinuxProcess, which uses the proc filesystem to make it easier to monitor processes with Ruby. Enjoy!

After six months, I’ve finally tested for pre-third kyu. Sophie was amazing, practicing techniques endlessly, putting up with hundreds of bad throws, and smiling through it all. Thanks to good teachers and hard work, the test went beautifully. I’m really happy about the whole thing: techniques feel more natural, timing comes easier, and now that it’s over, I can take more time to work with beginners! There are a couple of new students who are putting in a lot of hard work, and I’m really excited about how fast they’re learning. I hope some stay!

Being treasurer has been an adventure this term. I finally got the budget figured out… kind of… and then the test came! Proofreading all the paperwork then accounting for various fees and forms took several hours last night, but I think it’s finally in order. Now that I’ve fumbled my way through this test, I think the next ones are going to go a lot better.

The physics ultimate team, Physbee, is still undefeated! The last few games have been spectacular: playing an hour before dusk, the light rolls over the clouds and sweeps over the whole campus. I wish I had real shoes, though: much as I love my hiking boots, they are not the best for sprinting. ;-) Maybe I’ll try and get some this weekend.

O battle-scarred Guildmistress!

I engaged and killed a redheaded tall person in the CMC lab. I left two taped nerf darts, black with orange tips, and Kennedy's grenade.

I then returned to Nourse, where I came up the stairs to third only to find myself in the middle of a firefight--Kristine and Reid firing from the lounge, and Grace, Berlinm, and Brucenta on the other end of the hallway. They retreated to the south stairwell, Kristine, Reid, and I advanced. I came down to second, and moved to the bottom end of the stairwell. I killed Berlinm and Brucenta with two perfectly placed nightfire shots to their respective breast and stomach, and engaged Grace at length.

Her tactical acumen was clearly evident, as she fired off salvos of rubber bands at my feet. Swiftly dodging each volley, I returned fire, missing her narrowly several times. Finally Kristine and Reid bravely threw themselves onto the unrelenting arrows of misfortune, sacrificing their love for the good of the Nourse cause. I ran swiftly up the stairs after she had unloaded her last rubber bands, and delivered the coup de Grace to her suddenly vulnerable chest.

Her screams of abject terror still resounding in my memory, I shared tales of triumphant adventure and misfortune with my largely now-deceased floormates, and retired to bed.

Yours,

--Aphyr

P.S. I'm sorry I killed your roommate. ;-)

P.P.S. If this tale of high adventure and glory did not satisfy your tastes and therein earn my pardon for accidental death of a civilian, O Guildmistress, then I fear my cause is lost indeed.

Our esteemed and glorious Guildmistress,

It is with a sad heart that I must convey to you this most recent news: I have been fatally shot in the side by an Enforcer. At breakfast in the LDC, I noticed a very wary Nate leaving the dining hall. I sat down at a far table, planning to don a mask after eating and induce the inevitable demise of one Mr. Morrow, his eponymous occasion having finally been reached.

Before being able to put my plans into action, however, Nate returned, wearing an ominous mask and wielding a fully loaded Maverick. I leapt to my feet, ran around to the upper dining hall, and drew my concealed lightsaber. Bullets were useless against this fearless oblivion personified, and as I blew through the heavy wooden doors at the entranceway, I felt his inhuman breath chilling the very air around me. Knowing my end was near, I duck, spun quickly, and made a cut across his arm, but alas, it was too late! His pistol had already fired, dispatching shards of deadly foam and rubber into my lungs.

The medics say it is too late for me: I wish these last words to reach you, O dark princess of carnage, and evoke within your paranoid heart echoes of the deftly vengeful spirit we Assassins all strive to attain.

Yours,

--Aphyr

I’ve updated Sequenceable with new code supporting restriction of sequences to subsets through some sneaky SQL merging, ellipsized pagination (“1 … 4, 5, 6 … 10”), and proper handling of multiple sort columns.

Verizon’s Site Finder redux got you down?

<cr:code lang=“bash”> aphyr@unstable:~$ dig foobar

; <<>> DiG 9.3.4 <<>> foobar ;; global options: printcmd ;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 36752 ;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0

The surprise beach trip with Andy last week was pretty darn fun, but it deposited some hefty chunks of dust onto my camera’s sensor. So, now I have to get it cleaned somehow, and it looks like cleaning supplies could run me $150! Since I’m leaving in a few days, waiting for shipping really isn’t feasible; I guess I’ll have to get it cleaned some place in town.

"Zoo-zoo?" A grungy, bespectacled young man to my left shouts across the train platform. A cyclist, rolling idly down the street on what is perhaps the smallest bike I've ever seen, takes notice. "A-zoo-Bomb!" The youth next to me concludes, and the two of them wave to each other.

"You going to the pile?" The first inquires.

"Yeah, I'm gonna hang there for a bit, and I'll be up for the first run," The cyclist drawls.

So, I'm back in town! That was fast!

Managed to get out of school okay: finished my two papers on time, and despite my notes disappearing managed to make it through finals without too much difficulty. The papers are actually pretty cool: for Philosophy of Physics I got to look at two accounts of the mass energy equivalence relation, and talk about how we revise the scientific process for education. I didn't get to explore that thread as much as I would have liked, but I did get to read all of Einstein's work on special relativity. I know it's been said before, but the guy's a genius. The reasoning itself is straightforward, but he makes these intuitive jumps that are very surprising unless you know where he's going.

My roommate for spring term moved out early in finals week. Or at least, he himself moved. Most of his stuff stayed behind, and the friends he said would come pick it up never arrived. Hence, at 22:00 the night before flying out, I found myself reluctantly dropping cubic meters of clothes, games, books, and food down at the Lighten Up donation area. That was kind of a tough break, and I hope his friend manages to save my roommate's stuff in time.

Over the past three terms, I've become aware of a strange connection between sounds and visual images in my mind. When lying in bed and trying to fall asleep, with my eyes closed and thoughts mostly empty, I frequently experience visual patterns in response to loud or sudden noises. The first time it happened, my roommate's Macintosh computer emitted an unexpected and loud 'bonk' noise as an alert. Simultaneously, a diagonally oriented field of wavy white and black lines flashed before my eyes. The intensity of the pattern varied smoothly from black to white, so no clear delineations were perceivable. I estimate that there were about twenty to thirty of these lines visible, to give some representation of their density.

The perception lay somewhere between reality and imagination; not a concrete object in the world, but also not a "minds eye" sort of projection. It's analogous to the experience of seeing whorls and cascades of shadowy color when you press on your eyeballs for a few minutes, except it occurred suddenly, and faded as quickly as the sound. It also feels like there's an extra component to the experience, as well: it's not just a field of lines, but a visual feeling of orientation. That bit is much harder to describe or even verify, but it does seem present.

At first I thought I was hallucinating, or deceiving myself. Yet the experience surprised me time and time again, and has been consistent: it's happened twice this week. Door slamming, alert sounds, even ceramic mugs being set down on a wooden desk: all have associated unique visual patterns. The intensity, orientation, density, and waviness of the lines seems correlated with the character of the sound: the mug, for example, evoked a short-lived, vertical, dense, and straight field of lines. Sometimes I see cross-hatching, or a simple uniform flash. I plan to record these experiences from now on, and will try to characterize the relationship in more detail.

For months now, my friend Justin has been trying to get me up to the cities, and, more importantly, to meet the people on the Equality Ride. While I can't hope to express what the ride is without having been on it, the best story I can offer is that of 50-odd young adults traveling around the country on two buses, going to college campuses which make life hard for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender people. Some universities have policies so severe, students may be suspended or expelled for supporting their gay friends or family. The ride aims to change this by, well, talking. Talking to students about their experiences with sexual and gender identity, explaining how their faith interacts with those, and challenging arguments that these identities are fundamentally immoral.

The other half of the ride is more a public relations effort: when schools refuse the ride access to campus, riders stand vigil at the sidewalk, walk around the campus borders, or deliberately trespass. At one stop, riders carried pictures of their family. At another, they left lilies to symbolize the suicides of LGBT students, and read those stories aloud. "All we want to do is talk," the campaign seems to plead, "and yet we are handcuffed and arrested because the school doesn't want their students to have this dialogue."

While I agree wholeheartedly with the Equality Ride's efforts to talk with students, this method of civil disobedience rests uneasy with me. I think it's disrespectful to invade a private property, especially as a part of an organized group. These colleges have the right to bar people from their property, and, perhaps to a lesser extent, the right to determine a code of conduct for students. Surely a college can enforce its own attendance criteria: for example, as a man, I wouldn't complain about being denied entrance to a woman's university.